Originally posted on Nauticapedia.ca in 2020 — cross-posted with permission.

I believe I am not alone when I state that I wish I had spent more time talking to my parents when they were still with me. When we are young, we are so filled with making our own individual ways that we do not realize they had lived through significant events that shaped our country’s history and had interesting stories to tell. Luckily, I have been able to reconstruct my dad’s working history in the northern retail fur trade for the Hudson’s Bay Company (also referred to as HBC or the Company) from his employment records and other research aids.

Fortunately, he took photographs of his time with the Company, from 1923 – 1944 (though mostly undated and uncaptioned), and I also remember the stories he told me first-hand. Additionally, helpful, was a summary of my dad’s HBC employment, recorded on a biographical sheet that the Company compiled for many of its employees. Selected photos relating to his HBC history are included in the following sections. These are supplemented by a more extensive compilation found in Appendices A-G at the end of this article.

Routes and Immigration to Canada

George Seater Mercer Duddy, my dad, was born in Leith, the port for Edinburgh, in Scotland in 1903. He grew up there, and in the neighbouring county of Fife across the Firth of Forth, from where he travelled across the famous bridge to school in Edinburgh. In 1923, lacking any opportunity of employment—even in his father’s own business—he elected to emigrate to Canada under the “harvester” program. This was a venture of the Canadian government that encouraged young British men to come to Canada to take on jobs in farming and resource

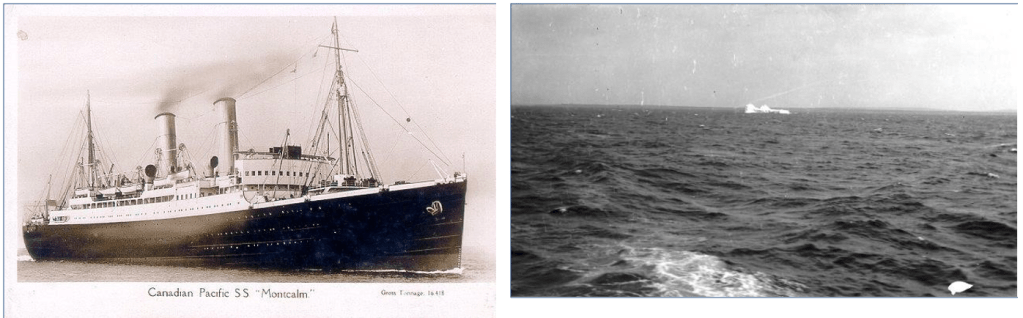

extraction industries. Arriving in Montreal on August 17, 1923 on the SS Montcalm, his first job was on a section gang with the CPR on the prairies. Photos shows a grain elevator and station believed to be at Frys Saskatchewan. Dad told me this employment was short-lived as he ended up breaking his leg. It is not clear how he spent his convalesce, perhaps it was at an uncle’s farm in Rivers Manitoba, but by September he was able to obtain a position as a fur trade apprentice with the HBC at Winnipeg. This was unusual as the common practise was to recruit most of their apprentices in Scotland. The articles, which he signed on September 25, 1923 required a commitment of three years.

Oxford House 1923-1925

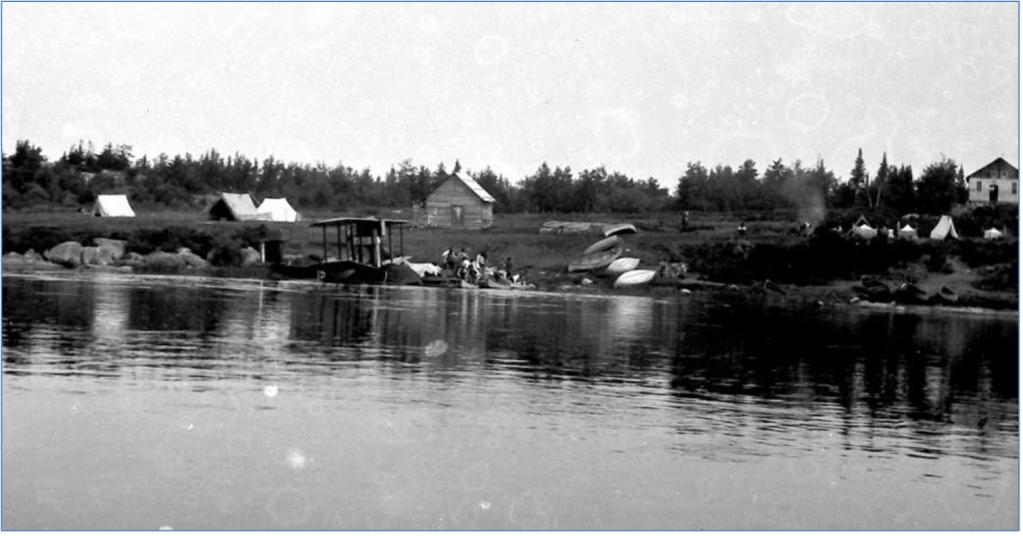

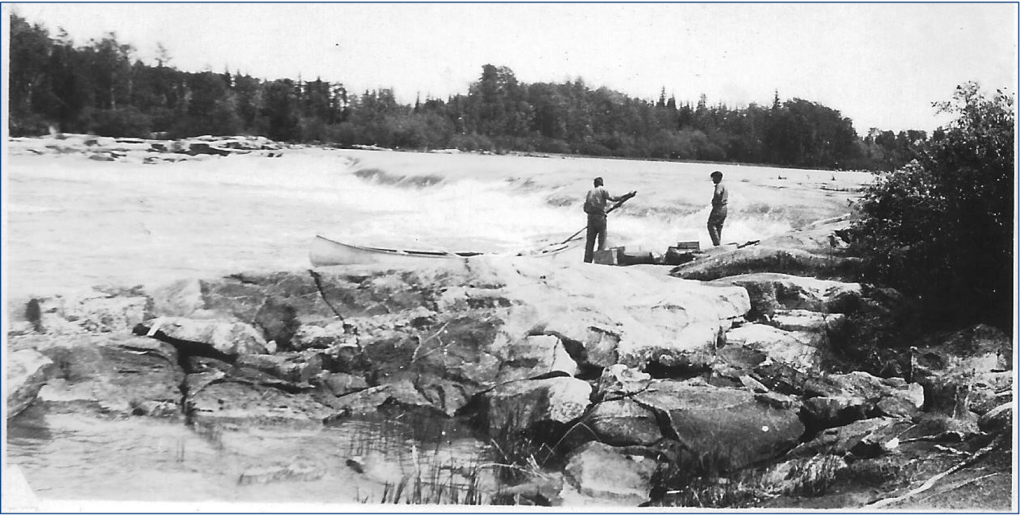

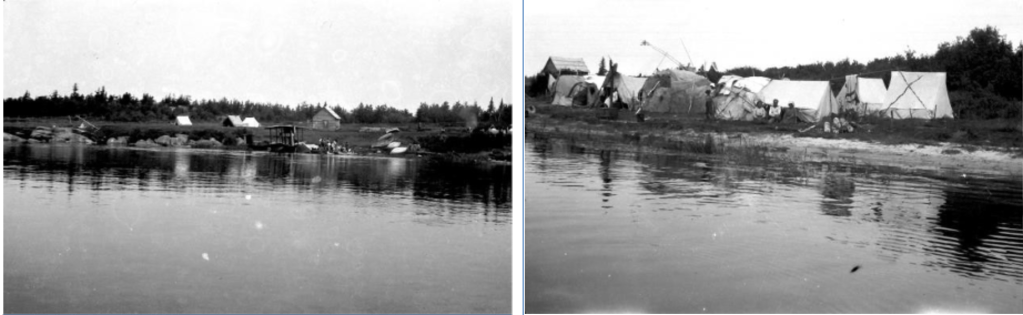

Until 1931, my dad’s employment was in what the Company called the Keewatin District. This Manitoba map shows the various locations he served (for the convenience of the reader). His first posting was to Oxford House on HBC’s original trade route from Hudson Bay to the interior of the vast lands (defined by its charter) draining into the bay of its namesake. The post was located on Oxford Lake between York Factory on Hudson Bay and Norway House near the head of Lake Winnipeg. The journey to his new home must have been an adventure for the new apprentice. It involved a steamer voyage up Lake Winnipeg of about 250 miles to Warren Landing, the site of the original Norway House, a short ride on a shallow draft tug to the present Norway House on Play Green Lake, and then a wilderness canoe traverse of three to four days through 130 miles of boreal forest along confused rivers, rapids, portages and lakes of the ancient Echimamish- Hayes River trade route to finally arrive at his new home on Oxford Lake.

Oxford House was the early post established in 1798 by Chief Factor William Sinclair as a way- point on the HBC’s main supply route that extended from York House on Hudson Bay to the vast interior lands (granted to it in its charter of 1670). At this post for nearly three years, my dad learned the skills to become a fully-fledged fur trader and post manager. By this time, Oxford House was simply a trading post supplied by lake steamer, York boat, or canoe from bases in Manitoba. My dad experienced Oxford House when it was a home to a community of Swampy Cree, Indigenous people who made their living from hunting, fishing, trapping and freighting for the HBC and the local United Church mission and others. In addition to the post, there was a mission run by the United Church and a few independent traders and settlers including an Irish independent trader named Sullivan.

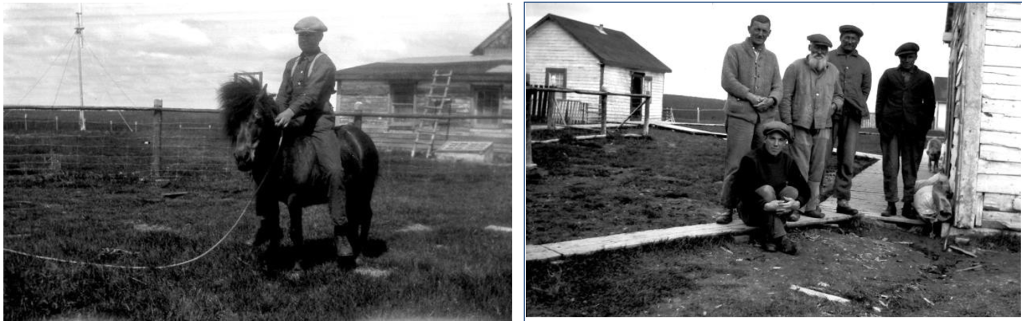

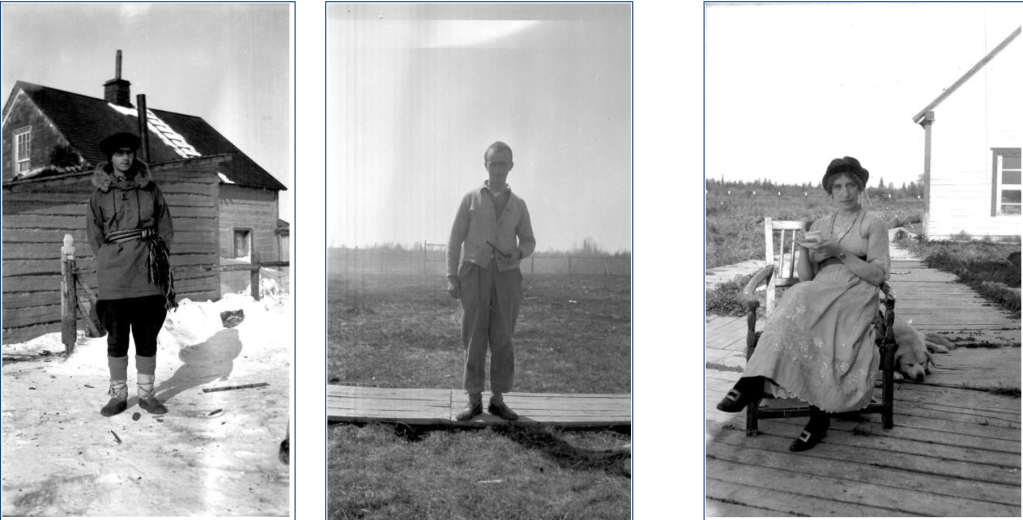

The post, an oasis in the boreal forest that included gardens and hay fields, was situated on a pleasant meadow enclosed by page wire fencing above the shore of the east end of Oxford Lake. From my dad’s photos, and a 1938 article from The Beaver (now known as Canada’s History magazine) “Huskies over the Ice” by Martin K Bovey, I surmise that the staff consisted of post manager W.F. Cargill, his wife, and son Sandy, a company clerk George Morrison, and a few local employees including an elderly, white-bearded Cree named David Monroe. Livestock included several sled dogs and at least one horse, used for retrieving firewood in winter and other purposes, a pony and a milk cow. The buildings of various ages and constructions with their numerous lean-to additions were grouped together in the enclosure except the post managers residence, which was set apart from the others. A high flag staff displaying the HBC flag predominated over the post.

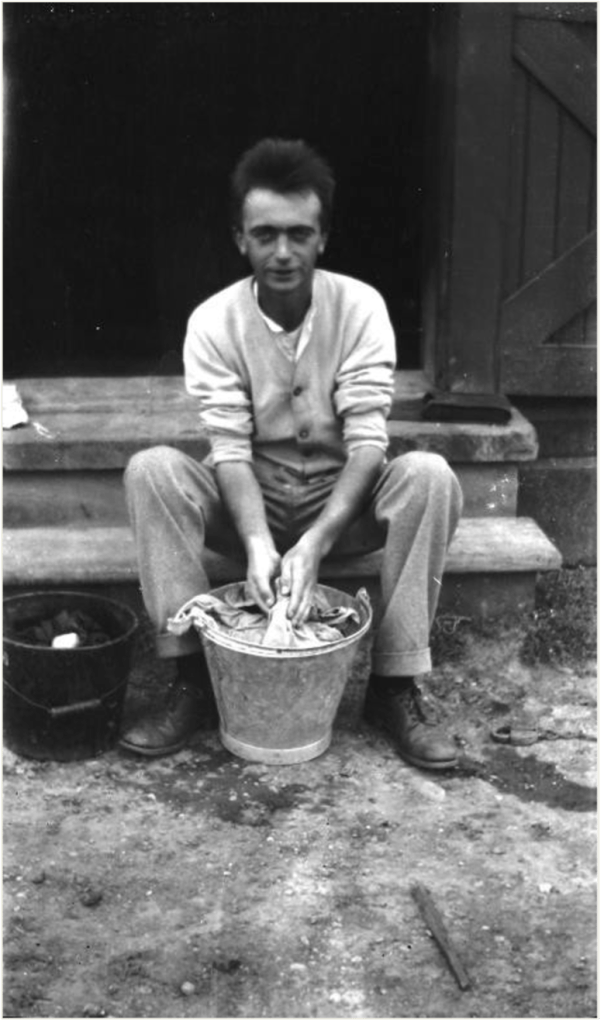

In addition to participating in the normal post activities of trading, grading and the baling of fur, there were the regular duties of preparing meals, maintaining buildings, caring for the dogs and livestock, growing vegetables and harvesting the hay to be attended to, and the incessant need for hauling of water and procuring firewood, both in summer and winter. As described in the Martin Bovey article, winter fur was taken to market by dog teams over long winter trails to Norway House and onto the Hudson Bay Railway. I have no knowledge if my dad participated in these long frigid ordeals with their winter camping but it is clear from his photos that he learned to work with dog teams in the winter and with canoes in the summer. The potential for socialization was limited; it stemmed from a small circle including the HBC post staff, clergy and neighbours in the community.

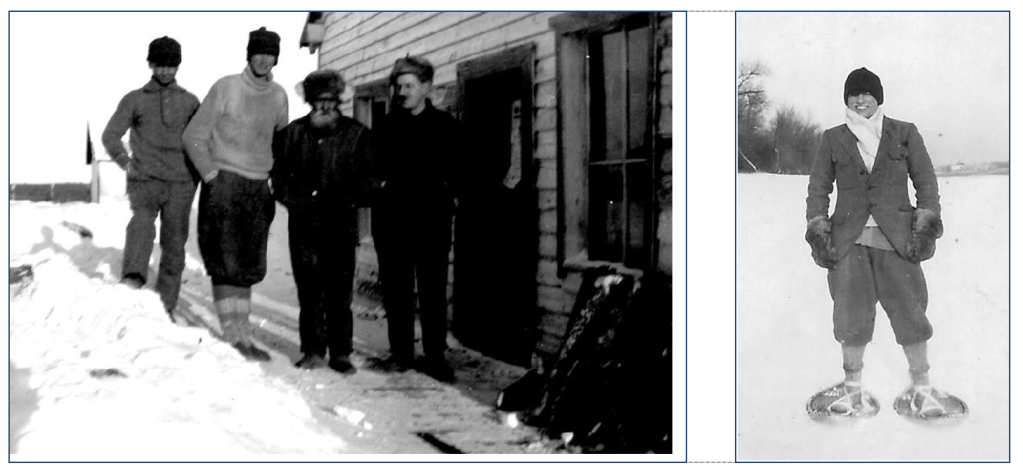

During his first winter, he (and the others) benefited from an enlarged social circle when Martin Bovey and Leslie Buck, two young American college student-adventurers, used the community as a base for their extensive winter adventures, including a trek made by Bovey to York Factory on the shore of Hudson Bay.

Amongst my dad’s photos I found a snap shot of who I assume to be Bovey. He must have sent it to my dad. It is noted on the back: “This is “me snow-shoeing on the Red River, Winnipeg (about 30 degrees below), I look happier than I felt I think.”

Oxford House, and its neighbouring posts in the Keewatin District, were visited by HBC inspectors to ensure the posts were properly run and records were maintained to the Company’s exacting standards. In winter this involved hundreds of miles of travel by dog sled. John Bartleman, whom my dad would encounter again later in the Mackenzie Athabasca region, was one of the inspectors at the time. His life with the HBC, and the rigors of his travels inspecting posts, are narrated (by Bartleman) in a 1961 interview.

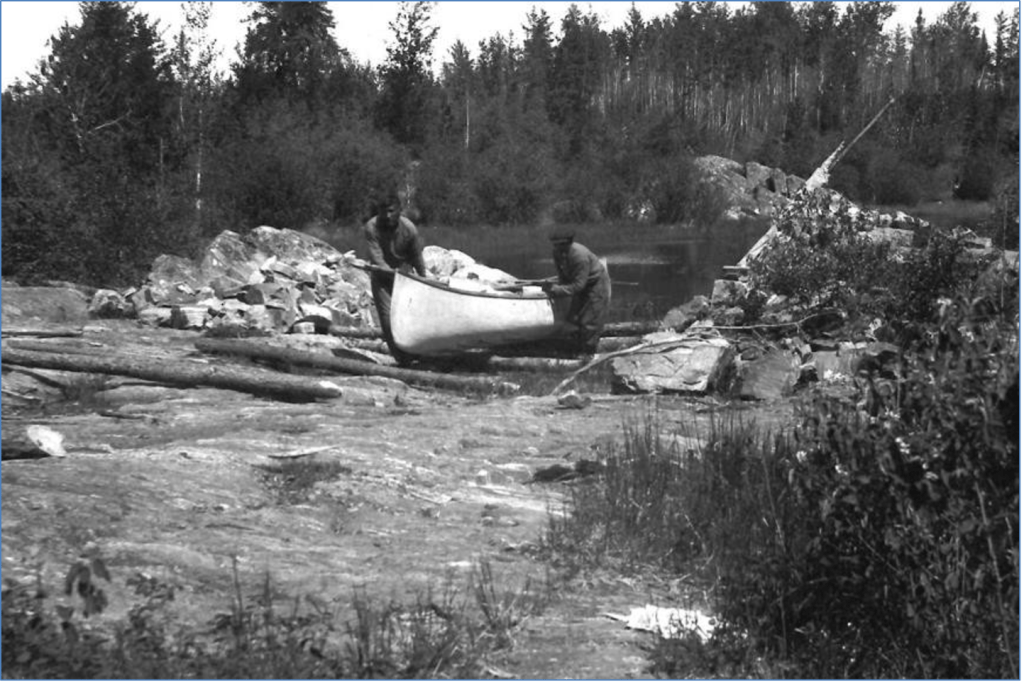

During the first summers, when my dad was at Oxford House, supplies arrived over the same difficult waterways he had first travelled in a canoe, came by York Boat, that unique delivery vehicle of the fur trade. After 250 years, with the advent of the outboard motor that could be used to haul strings of easily portaged canoes, the Company was finally giving up the use of these venerable craft and Oxford House was the last place they were used commercially. My dad was not a boastful person, but I distinctly remember him stating on several occasions that he personally had the honour of dispatching the very last brigade of HBC York boats. He saw them off from Oxford House on their homeward journey to Norway House, recording the event with the photographs found in his collection.

Little Grand Rapids 1926 – 1927

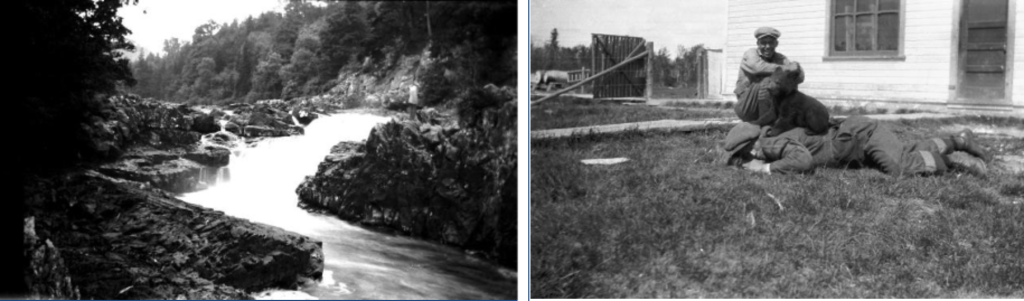

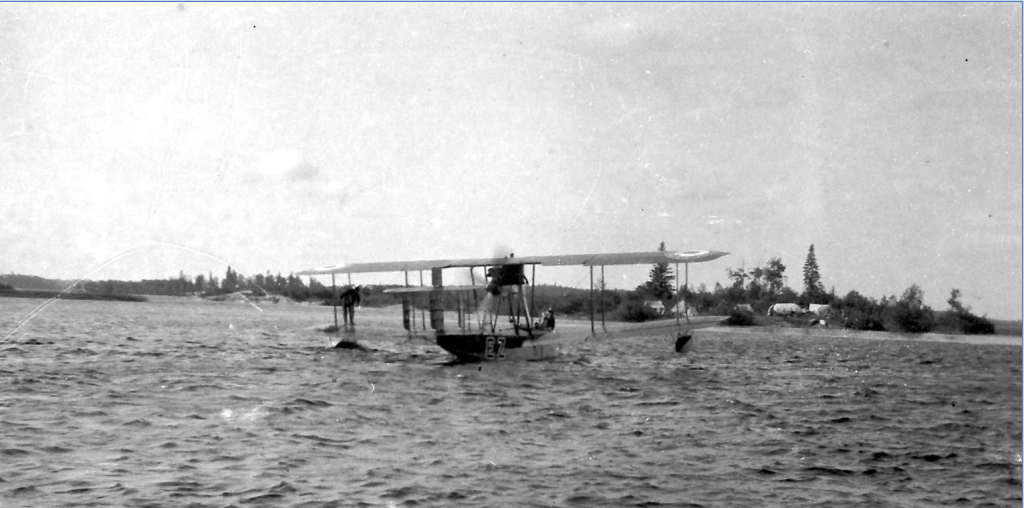

In 1926 my dad was transferred for a short time to the HBC post at Little Grand Rapids on Family Lake. The post is located east of Berens River Post on Lake Winnipeg only a few miles from the border between Manitoba and Ontario. It was reached by canoe through the rapids- infested Berens River. It must have been an interesting experience for him as the post at the time was serving as a base for RCAF fliers conducting pioneering aerial photography mapping. They were mapping river routes in the area utilizing Viking open-cockpit flying boats. Dominion Land Surveyor Knox McCusker, who my dad would later encounter as a well-known and respected resident of Fort St John, along with G.W. Malaher, were part of the operation putting in-ground control for the photography along the rivers. Prior to the commencement of flying, Malaher had to organize the difficult task of transporting gasoline from Berens River—incredibly, by canoe. An interesting article in Manitoba History describes this work.

Berens River 1926 – 1927

In September 1926 my dad received his first post manager position. This was at the well- established post of Berens River; a major steamship port-of-call on the east side of Lake Winnipeg. Located at the mouth of the river, bearing the same name, it was the home of community of Salteaux Indigenous people as well as both Catholic and United Church missions. Supplies for the Little Grand Rapids post and mission were landed here and transported 110 miles by hired Indigenous crews and involved dealing with fifty-three sets of rapids and falls up the picturesque river to Family Lake. Before my dad arrived, the York boats at this location had already been replaced by canoes.

At Beren’s River post my dad acquired his first motor boat. Fishing was pursuit he loved and one I later enjoyed with him in the waters of southern Vancouver Island.

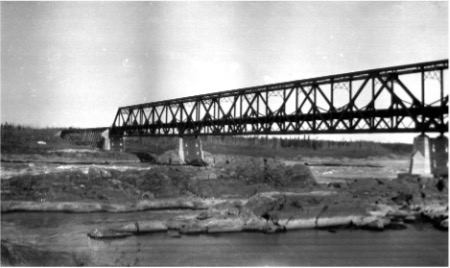

Gillam, Manitoba Mile 327, Hudson Bay Railway 1927- 1929

A new appointment as post management quickly followed in September 1927. This was a different type of assignment as it involved the establishment of a brand-new post at Gillam, Mile 327, on the Hudson Bay Railway. Interest in establishing a deep-water port on Hudson Bay had been revived after being mostly abandoned for more than ten years following the end of WWI. A decision to abandon the half-completed port facilities at Port Nelson, at the mouth of the Nelson River, and to build new ones at Fort Churchill was also made. At Kettle Rapids, the Nelson River had been crossed by a massive steel bridge but the railway had not been completed to Port Nelson. Soon efforts at repairing the incomplete railway grade and extending it to tide water were in full swing. Gilliam, at Mile 327, was a new settlement designated a divisional point on the railway. Along with yard facilities; a station, a hospital for workers and other buildings and accommodations were springing up. These included a new HBC store and staff house which became my dad’s responsibility. The new hospital was put to the test during the winter of 1928- 1929 when typhoid broke out amongst railroad workers and nursing staff were brought in to deal with the sick, and inoculate the healthy. They were proclaimed heroines for the efforts. My dad never made any direct mention of them but I have a sense that he was quite taken with one of these nurses.

The Pas and Fur Trade Purchasing Along the Hudson Bay Railway – 1929-1930

My dad’s next two postings were also associated with the Hudson Bay Railway. In 1929-1930 he was post manager at The Pas Manitoba, while in 1930-1931 he spent his time based at this location with the HBC Fur Purchasing Agency. This small community of about 4,000 people, (incidentally the largest Canadian town my dad ever resided in) is on the south side of the Saskatchewan River and connected to a CNR mainline via a bridge at Mile Zero of the Hudson Bay Railway.

Before my dad moved to The Pas, he took a well-earned vacation. I suspect he used some of this time to visit his Aunt Mabel on Vancouver Island. Mabel Seater, his maternal aunt and my godmother, had become part of the family of Sir Richard Lake, the former Lieutenant Governor of Saskatchewan. The Lake family, who at this time lived in Victoria, had established a pleasant summer home at Deep Cove near Sydney. It was a property I was to get to know well at the age of four when our family moved from the North to Vancouver Island. My mother, brother and two cats lived in a small cabin for several weeks there waiting for dad to wind up his affairs with the Company.

Little in his records relate to his experience at The Pas. I did find a Saskatoon Star Phoenix newspaper article of May 14, 1931 that reported his storehouse was broken into that morning while he was away at Sherridon.1500 musk rat pelts valued at $800 had been stolen. What he did tell me about was his experience with the HBC Fur Purchasing Agency as Fur Buyer when he would ride the train up the new Hudson Bay Railway to where the new port of Churchill was being constructed.

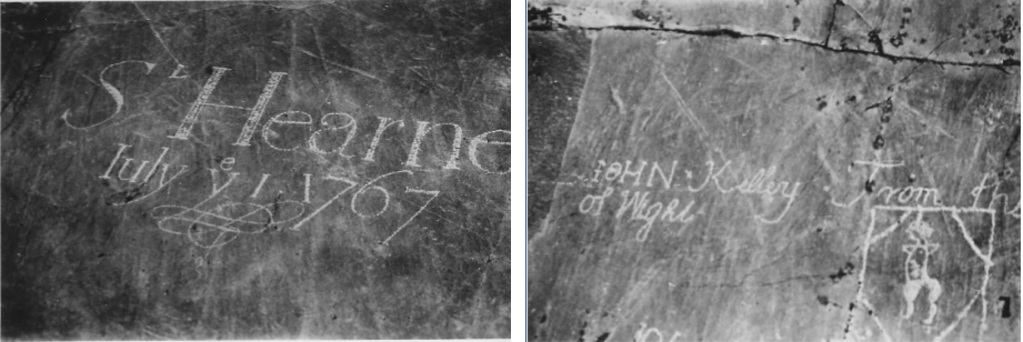

Trappers would bring their furs to the side of the railway and throw them into the baggage car through the open door. As the train progressed, my dad would grade them and bundle them. On the way back, the train would stop to allow him to pay each trapper. It must have been a very exciting time for him to see the vast Churchill Harbour project progress and to witness first-hand the old fortifications and cannons at Fort Prince of Wales. He documented, through his photo collection, daily life on the project, ruins and even shots of the famous 1767 Samuel Hearne inscription on a rock outcropping (Hearne was the first European to travel overland to the arctic coast and was later Governor, Fort Prince of Wales when it was surrendered to French).

Fort McMurray and the Athabasca River – 1931-1935

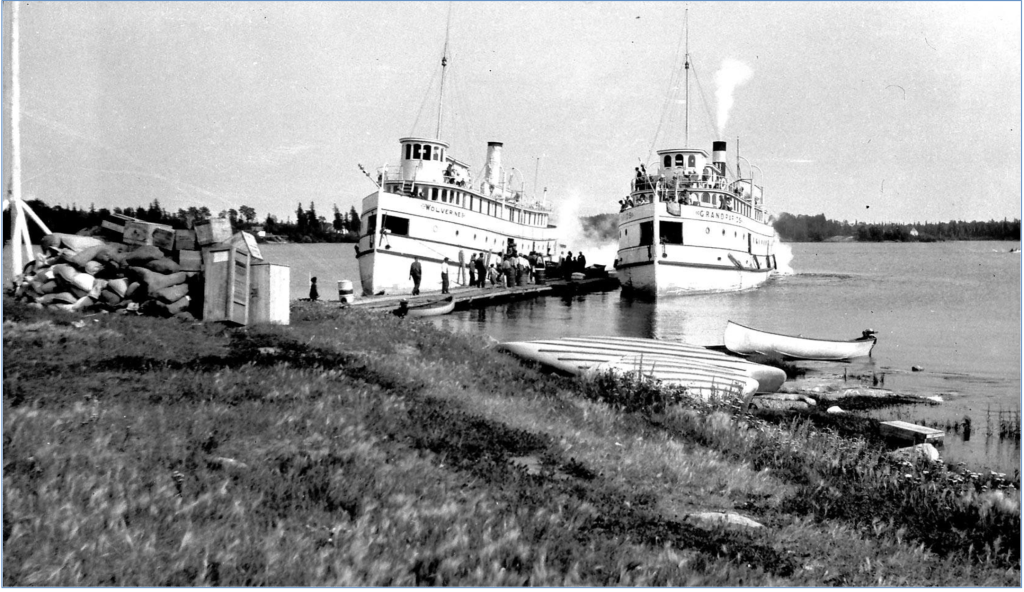

My dad’s employment with the company Fur Purchasing Agency, which ended in the spring of 1931, was his last in the Keewatin District. He would serve the rest of his work with the HBC in the McKenzie Athabasca District, in northern Alberta and British Columbia. These locations, (except that of LeGoff) are shown on the linked Alberta map. His employment records indicate that before he became Post Manager at Fort McMurray in the fall of 1931, he enjoyed a new summer adventure as purser for the Company’s McKenzie River Transport.

Interestingly, my dad never spoke of any experience on river steamers, but it is clear from his photo collection (specifically a picture of the Company’s store at Fort Fitzgerald and of the steamer Northland Echo docked there) that he reached the south end of Smith Portage leading to Fort Smith. Perhaps his duties were on the Echo or another vessel that operated from Waterways to Fort Fitzgerald. His experience this summer was a good introduction to the Mackenzie River, Canada’s longest and one of its mightiest river systems, and its importance as a vital transportation corridor.

The year 1931 was a tumultuous time for the Company in the west as it faced the Great Depression. Fur prices fell. The supply ship SS Baychimo disappeared after being abandoned near Point Barrow Alaska. Businesses collapsed due to the failure of mineral exploration and the loss of the key transportation link in the arctic regions. On the other hand, there was excitement as the Lindbergh’s visited Aklavik on their pioneering arctic flight, HBC steamers began to carry tourists along their Mackenzie River transits and a huge mining boom was developing on Great Bear Lake, which at the time was beneficial for pioneering bush pilots based at Fort McMurray.

While he was manager at Fort McMurray from 1931 – 1935, my dad would have spent most of his time transitioning the Company from the fur trade to retail merchandising. Adjacent to the Syn Branch of the Clearwater River, just before it enters the Athabasca River, Fort McMurray was becoming established as the head of air transportation for all of western Canada and the Arctic. This industry, and the essential river-shipping centered at nearby Waterways on the Athabasca River tributary the Clearwater River, were recovering from the depression and starting to prosper, fueled by the huge mining boom that was developing in the Great Bear Lake (that started in the early 1930s).

Bush pilots such as Wop May, Punch Dickens and Walter Gilbert, and their wives and children, were locals to the area and were as familiar to my dad as the retinue of agents, mechanics, delivery personnel and radio operators who were necessary to keep the community going.

Mostly young and well paid, they contributed to the economy and supported the many services the town provided including a hotel, restaurant, bank, post and telegraphic office and I think even a tennis court – I still have my dad’s old tennis racquet.

My dad’s tenure as a manager of the Fort McMurray post started with a momentous event that must have tested his resolve as the typical self-effacing Company manager. In 1930 the HBC London governing body appointed the accomplished businessman and banker Patrick Ashley Cooper as the new Governor (he was later knighted in 1944 for wartime service in WWII and other accomplishments). Imposing in both stature and social outgoingness, he shocked the staid establishment by setting out to personally visit a number of posts, his intension to draw together this outlying empire by inspiring teamwork and company loyalty. He used what ever

transportation method was available but soon found that aircraft and the HBC arctic supply ship Nascopie could take him to locations that London-based officials had never visited. These visits, reminiscent of those of George Simpson, and often in company with his wife and/or a cadre of senior company officials, were done in flamboyant style with lots of publicity covered in the press and the Company’s own Beaver magazine. Progressive in business practices but steeped in the traditions of the Company, he plunged into the task of sizing up the fur trade aspects his new empire in the Spring of 1932. His first focus was the Athabasca region and the first post he visited, on an aerial reconnaissance from Edmonton, was my dad’s store at Fort McMurray.

As described in the Beaver article of December 1932, it was dad who met the Governor’s party for the inspection of his post and the navigation facilities at nearby Waterways, fed them lunch and set up an audience with local towns people. Knowing my dad, I can image that the event was not the highlight of his career, what with some of HBC’s highest officials pawing his merchandise, poking into his stock room, scrutinizing inventories and reviewing financial records. I can imagine, after they left the area, my dad probably downed a few drams of the Company-brand Scotch after hanging his best suit back in the closet.

G.S.M. Duddy must have passed muster; in 1934 he saw the old HBC store, dating back to 1875 and located near the west end of Franklin Avenue, replaced by a larger, more modem and commodious building located further east on the same road. A large party and dance were held to celebrate the opening. As noted in the September 1934 Beaver magazine: “Mr. Duddy, the manager, was kept busy in winding up his faithful gramophone…”

In 1934 a large fire destroyed much of the town including the original Franklin Hotel. As reported in the Winnipeg Evening Standard for 16 July 1934, my dad became a local hero for saving his store.

My dad’s time at Fort McMurray ended during the summer of 1935 when he went on furlough. After twelve years in Canada he was finally able to return to his native Scotland to visit his family. His respite ended on 30 November 1935 when he again sailed for Canada, this time aboard RMS Duchess of Richmond, arriving at Halifax on 7 December 1935.

LeGoff Alberta – 1935

On his return my dad was posted to a small rural store at LeGoff Alberta to fill in for Ian MacKinnon (of Cambridge Bay fame) who had to go on medical leave. It was not a very busy location and produced little trade – probably a lonely situation for a young man. He noted on the back of one his photographs: “1936 at LeGoff, Alberta, shortly after my return from leave relieved here for 9 months, then closed it up”. After finishing this task, he moved to his next and last posting with the HBC.

Fort St John British Columbia – 1936 – 1944

My dad’s final posting for the HBC was at Fort St John, one of the oldest settlements in British Columbia. Here, as at Oxford House, he was on an historic fur trade route, this one established by Alexander Mackenzie of the Northwest Company (which before it was absorbed by the HBC was its most bitter rival). Fort St John was first founded as a fur trading post on the banks of the Peace River in 1794 (Fort St. John North Peace Museum research). Later, in the 1930s as homesteaders arrived to take up the rich agricultural land, the focus and location of the HBC post evolved from the fur trade business to a more agricultural-based one. When my dad arrived in 1936, the post had already been moved many times, and then was located at Fish Creek, north of the current town. It was remote from the earlier placements which had been on the banks of the Peace River, first served by fur canoe and boat brigades from the east and then by river steamer from the town of Peace River in Alberta.

In accordance with North Peace Museum records, my dad succeeded F.J. Sequin but HBC records indicate that renowned long-term manager Frank Beatton and his son Johnnie were still part of the staff. HBC records indicate that Johnnie Beatton (sometimes spelt by his family with only one “t”) was interim manager between Sequin and my dad. It was the elder Beatton who had moved the post to the present location from the river in 1927 and was earlier responsible for ongoing peaceful trading with sometimes hostile and rival indigenous bands. Frank was an employee until 1938 when the new store opened, and Johnnie stayed on afterwards to work in the new store. Johnnie Beatton remained a family friend throughout the rest of my dad’s life.

Road access in the area improved in the area after my dad’s arrival. When he first arrived, summer pack trains still set out for remote posts, including Hudson Hope and those north of Fort St. John, and dog teams were used in the winter. Soon after the completion of a bridge over the Half Way River in late 1938, my dad was able to claim that his was the first car ever to travel to Hudson Hope. A new store was opened at Hudson Hope around this time and is now the site of a local museum.

In September 1938, my dad opened the Company’s brand-new commercial store on 100th Avenue at the present townsite. The store was very similar in design to the one he had left at Fort McMurray.

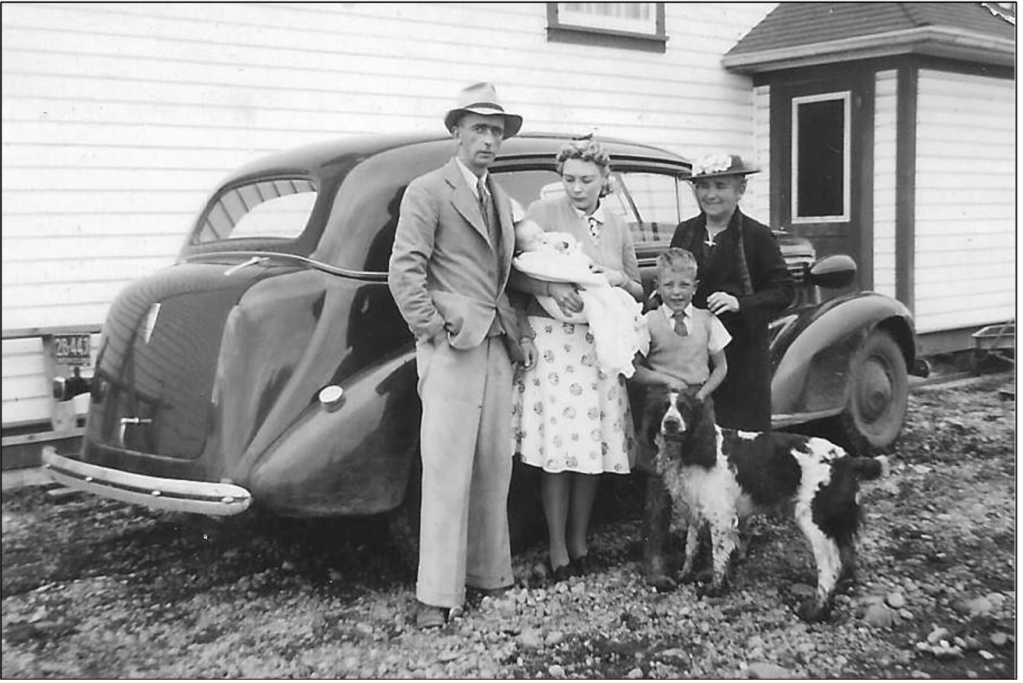

By this time my dad must have been getting used to new things; he had opened three new stores for the HBC and at some point, in 1938-1939, acquired his new 1938 Chevrolet car, but in the summer of 1939, there was something that was even more important: he acquired a new family. How it was worked out was never revealed to my siblings and myself, but it started (from our prospective) when my mother and her six-year-old son Paul arrived in from England.

They met in Edmonton where they were married and my dad made arrangements to adopt Paul. Along the way they acquired a Springer Spaniel dog, named Laddie, who “flowed” into the car when the door was opened to him. Soon my mother, who was used to jumping on and off London buses in high heels, was greeted by wooden sidewalks and muddy streets typical of a frontier town, where water was delivered, and the bath room was an outhouse. Aided by warm- hearted and generous neighbours, she soon adapted and formed friendships that lasted throughout her life. In 1940, Dr. Kearney delivered the family another son—me—at Providence Hospital. Initially we lived above the store but later moved to small house nearby where my mum had a big vegetable garden, kept chickens and raised angora rabbits.

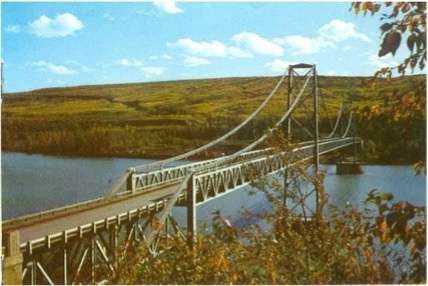

World War II had a profound effect on transportation and delivery systems in the Peace River area with the construction of the Alaska Highway. Even before then horse pack trains, overland winter transportation by dog team, horse sleigh trains, and tractor trains, were all fighting their way north to fur posts, river-forwarding locations and future air field locations like Fort Liard, Fort Nelson and Sikanni River. While heavy winter hauling was evolving from horse-drawn bob sleds and cabooses to tractor trains and trucks, Grant McConachie was developing his pioneering float plane service to the Yukon, with its local base at Charlie Lake, into a fully land-based fleet, starting as Yukon Southern Airways and eventually becoming Canadian Pacific Airlines. The basic airfields he was establishing would soon be taken over and expanded by the Canadian government, even before the Alaska Highway construction began, to eventually become part of the strategic Northwest Staging route. Beginning in 1942, the old trade route where we lived at Fort St. John was crossed by the brand new one. Large US Army camps were established nearby, as construction of the highway and airfields reach northward. The new Peace River Bridge was underway, and the small town quickly expanded as trucks trundled up the new road day and night.

In 1943, my parents made a long road trip to Vancouver Island to visit Aunt Mabel via Jasper, Banff, along the lonely Big Bend Highway and through the precipitous nightmare-evoking Fraser Canyon, while Paul and I stayed with Lucy and Maney Scheck at their farm; Lucy and her sisters Irene and Sylvia (the Lohman sisters) all worked at the HBC store at various times. We were told it was a delayed honey-moon trip but our parents had other plans afoot. With over twenty years of service with the HBC in the north, a growing family with needs of better educational opportunities than afforded in the Peace region, they decided to leave the Company and purchase their own grocery store on southern Vancouver Island. Although it was not a factor in their initial decision, the HBC’s unilateral decision to cancel the pension plan of long- time employees must certainly have reinforced their decision. Onwards to new adventures, it was sad, however to leave behind many wonderful friends.

My mum was a great communicator and continued to stay in touch with many of their northern friends for the rest of her life. In our new home in Metchosin, we were graced by visits from Doc and Nan Kearney, Duncan Cran, Delia Cuthill and Lucy Scheck. As long as my dad could still drive, he took my mum to the Okanagan where Delia and my mum enjoyed doing pottery together. When I worked at the Bennett Dam, from 1964 – 1967, they made two trips to see me and then carried on to warm welcomes in Fort St John. The Peace is a beautiful area with wonderful people, I am grateful to be rooted there and to have later worked in the region, and even had to the opportunity to visit with the Scheck family, Mrs. Bowes, Duncan Cran and Doc. Kearney.

Conclusion

Over the years I have learned that what may be looked back on as just ordinary daily life by some—especially by those living that life—may later prove to be quite remarkable in the eyes of others.

The piecing together of my dad’s life in the fur trade, while personally rich for myself and hopefully for my family as well, will perhaps be of interest to others. The narrative and photographs reflect western Canada’s rapidly changing history in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s as the world moved from a World War I recovery and then fell into the grip of another war.

During my dad’s service, HBC, as Canada’s oldest company, evolved from its fur trade roots to a largely retail establishment. The York boats and pack trains largely disappeared from the old supply and brigade routes, while new routes intersected and replaced the old ones.

Transportation into the north was vastly improved with the introduction of the outboard motor, sturdier constructed vessels, and by the development of ports, railways and roads. The lands of the Peace River, once the preserve of the indigenous hunter and trapper, increasingly gave way to the homesteader and farming. The advent of the bush plane and radio communications revolutionized the north and permitted mineral exploration and development into remote regions such as Great Bear Lake. My dad felt privileged to know many of the trappers, traders, surveyors, bush pilots and pioneer farmers and businessmen of this era. He even had an encounter with the Company’s most senior officials. At times I am sure it was a lonely life for a single man, as the north perennially lacks compatible single women for socialization, but overall, it seems that the twenty-one years he spent with the HBC was rich in terms of experience.

As a final note, I realize there may be errors in identifying the persons appearing in some of the photographs. I could have simply avoided this problem by not providing any names at all but decided to give my “best shot” at it to make the account more real. If anyone notices errors or can provide additional information I would appreciate if they could leave me a message through the Nauticapedia.ca website.

Acknowledgements

All photos, except where noted, are from the author’s family collection. I would like to thank James Gorton of the HBC Archives in Manitoba and Heather Sjoblom of the Fort St. John North Peace Museum for their help with research and my Nauticapedia.ca colleagues and friends John MacFarlane and Lynn and Dan Salmon whose hard work and dedication made the publication of the article on the web possible. I am especially grateful for Lynn’s masterful editing of the text and layout which elevates the presentation to an higher level than I am capable reaching on my own.

APPENDIX A – EARLY DAYS IN CANDA

APPENDIX B – THE JOURNEY TO OXFORD HOUSE

APPENDIX C – LIFE AT OXFORD HOUSE

APPENDIX C – THE LAST YORK BOAT BRIGADE AT OXFORD HOUSE

My dad maintained that he dispatched the last-ever York Boat Brigade circa 1925.

APPENDIX D – LIFE AT LTTLE GRAND RAPIDS

APPENDIX E – LIFE AT BERENS RIVER

APPENDIX F – LIFE AT GILLAM

APPENDIX G – SIGHTS AT CHURCHILL

Leave a comment