Originally posted on Nauticapedia.ca in 2019 — cross-posted with permission.

Introduction

Propelled by the fur trade, the Port of Vancouver played a pivotal role in the establishment of Canada’s presence and sovereignty in the western Arctic that lead to the founding of settlements along the Northwest Passage. This article describes the hazardous voyages and key events of this enterprise over the span of nearly two decades from 1914 – 1933.

Except for a shipment made by Captain Christian Klengenberg in his schooner Maid of Orleans in 1926, the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) was the only business to use Vancouver exclusively for arctic supply. The HBC was a late-comer to the fur trade in the western arctic, entering after 1913 when fur commissioner R. H. Hall realized the company was missing out on the valuable arctic fox trade. It soon became apparent that ocean transport around Alaska was cheaper and more effective than their Mackenzie River supply system. Thus, Vancouver became the prime source of supply for this trade, with Pauline Cove on Herschel Island (just east of the Yukon – Alaska boundary) as the primary destination port. The HBC experimented with overland supply from Hudson Bay in 1928. However, ocean shipping continued until improvements were made to the Mackenzie River transportation, and the port of Tuktoyaktuk was established on the arctic coast (near the eastern side of the Mackenzie Delta) in 1934. With this improvement, regular voyages from Vancouver were halted, and most shipments were made via the Mackenzie River system—with goods consigned to Tuktoyaktuk.

During this same period, Captain Christian Theodore Pedersen was the HBC’s main competitor in the western arctic. He was employed by H. Liebes and Co. of San Francisco until 1923 when he formed his own firm known as the Northern Trading Company. In 1936 this firm, and its Canadian subsidiary the Canalaska Company, were sold to the HBC and the assets —the fur- trade posts and Pedersen’s last Canadian-registered ship—were integrated into HBC operations. Pedersen’s interesting story is fully explored in the Nauticapedia.ca article: “Captain Christian Theodore Pedersen and the Western Arctic Fur Trade” by Captain Sven Johansson with contributions from John MacFarlane.

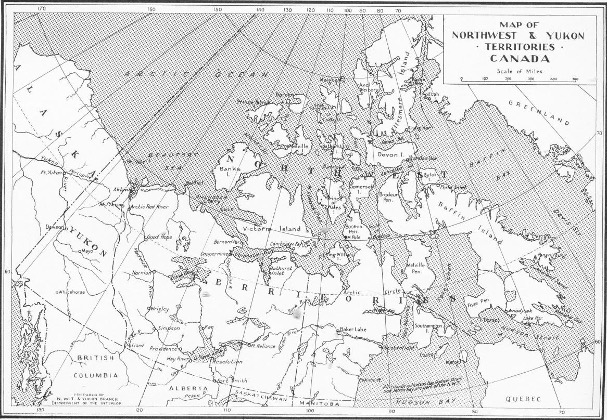

The Nautical Highway to Herschel Island and Canada’s Arctic

The route to reach Herschel Island in the western Arctic from the Port of Vancouver was a challenging 3,600-mile transit. Vessels departing Vancouver proceeded out the Juan de Fuca Strait then followed a great circle route to the Bering Sea via passage through the Aleutian Islands. After transiting the Unimak Pass near Unalaska, ships passed through the Bering Strait to enter the Beaufort Ocean. Alternatively, ships might travel via the Inside Passage waters to the north end of Vancouver Island or northwards to Prince Rupert before crossing the often storm-wracked Gulf of Alaska. The passage around Point Barrow was fraught with danger. It was difficult and uncertain due to the presence of pack ice most of the year. In the summer, it usually receded from the shoreline permitting a navigation window between mid-July to mid- September and allowed experienced—and lucky—navigators to make their supply runs into Herschel Islands and beyond. For ships assembling near Point Barrow to make the run, it was a great source of pride to be the first to reach Herschel Island. Pauline Cove on Herschel Island presented the only safe anchorage on the arctic coast for large ships. The community was first established in 1890 by over-wintering whalers pursuing bowhead whales.

A Brief History of the Settlement of Herschel Island prior to 1913

A large Euro-American component had settled at Herschel Island, mostly San Francisco-based Americans, hunting bowhead whales for their oil and baleen. In 1893 the Pacific Steam Whaling Company (PSW Co.) constructed buildings on the island that remain today. The ‘community house’ contained a recreation room, an office for the manager and storekeeper as well as storage facilities. The adjacent ‘bone house’ warehoused whaling products—and was later the site of the infamous hangings of 1924 (Corporal Doak of the RCMP and HBC Tree River post manager Otto Binder were murdered and the culprit was brought to justice and hung). In 1893- 1894, at the height of the whaling industry, the population on the island was estimated at 1,500 residents making it the largest settlement in the Yukon at that time. As whaling neared its end, due to a diminished population of the mammals and a collapse in demand for whale products, the PSW Co. buildings were lent to the Anglican Church from 1896-1906.

Lacking any formal Canadian presence, the residents of the island operated as a freewheeling frontier outpost under ‘whaler’ law and justice. This practice changed when the Revered Isaac Stringer of the Anglican Church of Canada arrived about 1893. Noting the rampant use of alcohol and abusive employment by the whalers of the local Inuvialuit (men as meat hunters, and women as clothes-making seamstresses), he successfully induced the Canadian government to establish a police presence on the island. In 1903 Northwest Mounted Police (NWMP) Inspector Francis Fitzgerald visited the island. The following year he and Constable Sutherland established a detachment on the island, housed in two sod huts, until better facilities could be found. In 1911 the police purchased all of the assets of the PSW Co. including the ‘community house’ that had been on-loan to the Anglican Church.

As the NWMP had done on the southern border of the Yukon, at the Chilkoot and White Passes during the gold rush, a handful of dedicated policemen were able to bring about the orderly and mostly peaceful establishment of fur trading settlements in the arctic. This was accomplished by using Herschel Island as the base and reaching eastern outposts with long-distance patrols. Their presence helped ensure Canada’s sovereignty over a vast arctic region. To put the scarcity of the population and the geographic vastness of their task into perspective, it was reported in the June 1922 edition of the Beaver magazine by RCMP (the NWMP changed names to Royal Canadian Mounted Police in February 1920) Inspector Wood that along the 1,200 mile coastline from Herschel Island to the eastern end of Coronation Gulf, including King William Island, the native population consisted of just 1,364 people. This would be equivalent today of the student body of an average high school being distributed in small groups along the Trans Canada Highway between Vancouver to a point just east of Regina Saskatchewan.

The Hudson’s Bay Company enters the Fur Trade in the Western Arctic 1912 – 1913

When the HBC finally established satellite trading posts in the Mackenzie Delta (at Aklavik and Kittzigazuit) in 1912, American traders had already been operating from ships and schooners east of Herschel Island. These individuals included: Fritz Wolki, Martin and Ollie Andreasen (brothers), Joesph Bernard, and Christian Klengenberg. By 1913 only a few traders still participated in the whaling industry. The luxuriant fur of the arctic fox (also referred to as the white fur fox) fuelled a new fashion craze and had already created another economic boom now that the whales were no longer the major export they had once been. Brief excitement was also generated by Vilhjalmur Stefansson with purchases and employment for the Canadian Arctic Expedition (CAE). Prompted by suggestions from famed arctic explorer Raold Amundsen (Gjoa) and Klengenberg’s experiences with the Copper Eskimos, Alaskan-based trappers, many of them former whalers (already engaged in the arctic fox fur trade in Alaska and neighbouring Siberia), began entering Canada in search of the highly valuable white fur of the arctic fox.

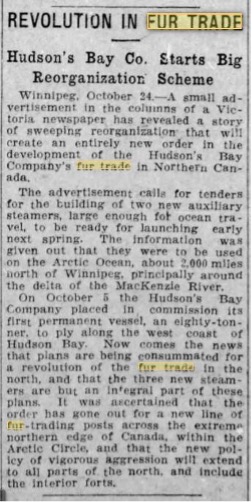

Prior to 1912, when the HBC first established satellite posts in the Mackenzie Delta, they confined the main extent of their northern Mackenzie River trading to the fur bearing animals of the boreal forest regions. Although downriver Inuit sometimes ventured upstream for trade, the limit of the HBC’s river-supplied network was, for the most part, the areas serviced by their trading post at Fort McPherson on the tributary Peel River and the Arctic Red River post on the main stem of the Mackenzie. Realizing they were missing out on valuable trade and would require ocean transport (to be competitive with the supply of trade goods and supplies and post building materials), the Company publicly announced in 1913 that they were entering the arctic fur trade in a major reorganization and would establish new posts within the arctic circle with “vigorous aggression”.

An article in the Daily Colonist on November 8, 1913, expressed that the city of Victoria was favoured to be the base of the western arctic expansion and two ocean-capable vessels were to be built for the trade. However, things did not work out entirely that way and only one was constructed – perhaps because of the changing fur markets and shipbuilding priorities caused by the start of WWI. In any case, only one company-owned vessel was built: The 58-foot auxiliary schooner Fort McPherson launched by Vancouver Shipyards in 1914. (The name painted on her stern by the builder was Fort MacPherson but references to her usually cite Fort McPherson – without the ‘a’ in Mc) The Fort McPherson was designed to distribute cargo brought to the Arctic by larger ships and was the first Canadian-built and registered ship to enter the western Arctic to ultimately reach King William Island—one of the most remotely inhabited areas on the earth. During her working life, from 1914 -1930, this sturdy and reliable schooner was an important tool of the Company in establishing western arctic trading posts from Herschel Island and throughout the Northwest Passage.

These posts were the foundation of permanent settlements in the Arctic. Regularly supplied fur posts beyond the arctic circle extended almost entirely across Canada’s arctic oceans and by 1929, company ships had finally navigated the Northwest Passage first transited by Amundsen in 1906. The location and in-service dates of posts serviced by the Vancouver supply ships from 1914 – 1932 is shown in Appendix B.

The Chartering Years 1914 – 1920

Although the HBC’s foray into the arctic was led by the Fort McPherson, most materials destined for the HBC posts and police detachments in the early days were carried by American- chartered ships. Under the command of experienced ‘ice’ captains, men who had previously been involved in the whaling trade, their cargos included building supplies, fuel, boats, living supplies and trading goods. Four such voyages were made in vessels owned by Captain J.E. Shields and Captain Louis Knaflick, both of Seattle. For several years prior to 1914 they had freighted into the Bering Sea area with their 78-foot power schooner Bender Brothers. After the 160-foot Ruby joined their fleet in 1914, she was chartered by the HBC to make the initial passage north to commence their arctic expansion. An article in Vancouver’s daily newspaper The Province describes the voyages of these two vessels. Contrary to some reports, the McPherson left first, on June 13, a full month ahead of the Ruby. Captain Otto Bucholtz and his six-man crew took her through the inside passage. Ruby took aboard stores and fuel at Seattle then proceeded to North Vancouver to load a huge cargo of goods including 135,000-board feet of lumber. The supplies were intended to satisfy the HBC’s needs for three years. Ruby also carried supplies for the Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNWMP—the name used from 1904 to 1920) detachment at Herschel Island, and also for an independent trader at Baillie Island, her final destination. Before Ruby sailed for the arctic on July 13, she was joined by Chris Harding, the HBC Mackenzie River fur trade manager, his wife as well as other HBC personnel who were to build and staff the new posts. It is interesting to note that The Province’s writer, reporting on the departure, made this remark about the voyage.

“This is practically the first time that Vancouver had been a base of Arctic supply and opens up a new and expanding field to local merchants.”

Squeezing ice halted the progress of both ships twenty-five miles east of Point Barrow and damaged Ruby above the waterline. They were too late. Only the wily Captain Pedersen made it through to Herschel Island that year. Ruby and McPherson retreated to Teller, Alaska. Ruby’s cargo was put into storage ashore and she returned to Seattle for repairs and to pursue other cargos. Departing with her were Captain Bucholtz and two members of the Fort McPherson’s crew. The Fort McPherson was put into winter quarters and the remainder of her crew weathered-over at Teller during the winter of 1914-1915 to oversee the vessel and the cargo ashore. These men were the Hardings, Ernest P. Miller, and two Danes: Heinrich (“Swogger”) Hendrickson and Rudolph Johnson (who would later captain and be the engineer of the Fort McPherson).

Ruby returned to Teller on July 15, 1915 captained by S. F. Cottle, a more experienced ice master. An article in the December 1977 issue of The Sea Chest by Captain Ed Shields: Aux. Schooner Ruby – Arctic Supply Voyage describes the voyage. Upon arrival she discharged her cargo to the Bender Brothers, before reloading the stored cargo. After Chris Harding and his wife boarded on July 23, Ruby completed the passage to Herschel Island. She arrived there on August 14, moored alongside the beach near Fort McPherson and discharged the materials for constructing the new post at Herschel Island. On August 18, McPherson pulled alongside and materials for forwarding to the new post at Baillie Island were transferred to her. On August 28, Ruby proceeded to Baillie Island to discharge the balance of the cargo, for a trader reported to be “Wilkie” (more likely Wolki). From this point Ruby returned westward picking up cargo from other American traders in Alaska destined for Seattle.

During the return voyage to Seattle, she encountered a succession of gales that damaged her sails, and experienced motor trouble. Nearing the entrance to the Juan de Fuca Strait, the motor failed completely and she had to be towed into Port Angeles by the tug Snohomish. Ruby arrived home under tow on November 2nd.

An article in the April 28, 1917 edition of The Province indicated that the HBC dispatched some freight aboard the Ruby for the Company in 1916, but that she never reached Herschel Island. It is doubtful much was required as the southern party from the Canadian Arctic Expedition had departed the Arctic that summer and left behind lots of surplus supplies. The same article elaborated that the HBC contracted with H. Liebes and Co. for transport of materials in 1917, carried by the power schooner Herman (Captain Pedersen) from Vancouver to Herschel Island. An article in the San Francisco Examiner of September 20, 1917, informed readers of the return of the Herman following her delivery of supplies to Herschel Island. Pertaining to Liebes’ own trading, it said that Herman was prevented from proceeding eastward into Coronation Gulf because of adverse ice conditions.

From 1918 through 1920, the HBC again turned to Captains J.E. Shields and Louis Knaflick’s firm in Seattle for their arctic supply freighting. In 1918 and 1919, Captain S. Whitlam and the Bender Brothers was able to get supplies from Vancouver through to Herschel Island and return fur to Victoria’s Ogden Point docks in spite of difficult ice conditions. Aboard the Ruby in 1920, he made a record voyage, reaching as far as Baillie Island with supplies loaded at Victoria for the HBC and RNWMP. The cargo included building supplies for the establishment of new facilities on the Kent Peninsula. Laden with two tons of fur, Ruby’s return to Victoria on September 24th, marked the last use of the Seattle-based power schooners on this route.

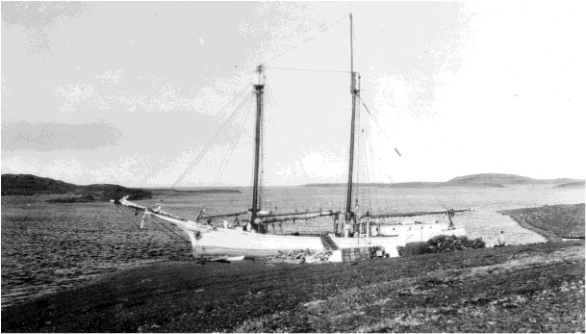

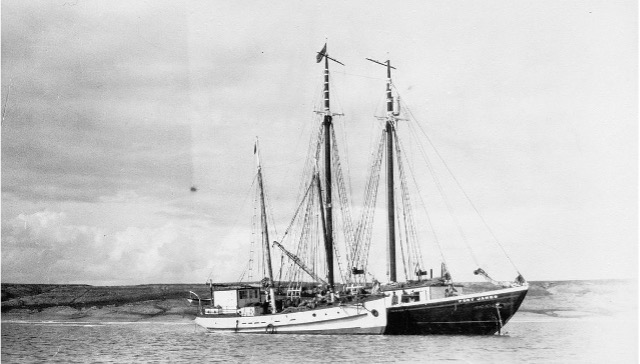

(Hudson’s Bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba. Arthur M. Irvine fonds, 2012/1/214 Schooner ‘Bender Bros.’ Herschel Island, [between 1919-1920].)

The Lady Kindersley Years 1921 – 1924

As economies recovered from the austerity of WW I and the world entered the roaring twenties, fur markets recovered and the HBC was finally able to pursue its dream of acquiring its own supply vessel for the western Arctic trade. Lady Kindersley, a 187-foot power schooner, was already under construction for use in the 1921 season. Named in honour of the HBC governor’s wife and boasting both wind and auxiliary power—three masts and a two-cycle semi-diesel engine—she was launched in Vancouver on March 26, 1921. Her sponsor, Frances Gladys O’Kelly, wife of HBC Manager T.P. (Tom) O’Kelly, broke a Champagne bottle across her bow. In her short life under Captain Gus Foellmer, Lady Kindersley made three successful voyages to the Arctic. Unfortunately, on her last voyage in 1924, she was trapped in the ice and was abandoned near Point Barrow Alaska.

The 1921 Voyage

Married couple Frances and Tom O’Kelly sailed on the vessel during her maiden voyage. The voyage was through the inside passage to Prince Rupert, and then past the Aleutian Islands, calling at Akutan, Nome and Teller before finally rounding Point Barrow and reaching Herschel Island on August 9. After unloading there, she proceeded to the Baillie Island post at Cape Bathurst, then onward through Dolphin and Union Strait to Bernard Harbour, a first for a supply ship of her size. Her final destination was the tiny settlement of Tree River midway in Coronation Gulf, where both the HBC and the RNWMP had established outposts in the protected anchorage near the river’s mouth. Details of the many adventures and firsts of the voyage, including the ship’s miraculous escape from the pack ice mid-way between Herschel Island and Point Barrow on their homeward journey, may be found in an amazing journal and an accompanying photographic album that Frances produced. These documents, including a typed transcription of her handwritten text, are available on-line from the Arctic Institute of North America and hosted by the University of Calgary. The journal offers a gripping account of her impressions of the human and animal populations encountered, the challenges of the environment and the inadequacies of the ship despite innovative repairs, and all other aspects of the voyage that proudly set-out, but limped home albeit with a fortune of arctic fur. Frances left a fascinating record that will be illuminating to anyone who cares to peruse it.

Notable passengers carried on Lady Kindersley’s outbound voyage included: Miss Roberts (the intended bride of G.E. Merritt who was the Anglican missionary at Bernard Harbour), Revered Geddes, district HBC inspector C.H. Clarke, RCMP Inspector Wood, and Corporal Doak (the latter individual was tragically murdered, along with HBC Tree River post manager, Otto Binder in 1922) The wedding took place in the salon of Lady Kindersley while the vessel was at Bernard Harbour with Reverend Geddes officiating and Frances as the matron-of-honour. Inspector Wood gave the bride away and Pete Norberg, C.H. Clarke and Tom O’Kelly served as witnesses.

Norberg later piloted Lady Kindersley to her final destination at Tree River with his vessel the schooner El Sueño under tow. Homeward-bound Lady Kindersley carried Harold Noice—known as ‘the youngest arctic explorer’—on the first leg of his return trip to Seattle. He was a former CAE member who was returning from a remarkable but lonely, single-handed expedition to the Kent Peninsula and Victoria Island. During this endeavour, he mapped the eastern shore of Victoria Island and collected numerous historical artifacts representing the area’s earliest civilization.

The 1922 Voyage

Captain Foellmer, wary of ice conditions experienced between Point Barrow and Herschel Island during a voyage that year which resulted in a late arrival at the island on August 30, proceeded no further with Lady Kindersley. He hastily dumped all the carefully stowed supplies needed for eastern posts and reversed course to beat a retreat westward to clear Point Barrow. This action created a supply problem for eastern posts as the only company vessel available at the time for forwarding desperately needed supplies was the motor schooner Fort McPherson.

In the Mackenzie delta, the RCMP moved its Fort McPherson post to Aklavik, which also replaced Herschel Island as its administration center for the Arctic. Coincidentally, the new river steamer Distributor extended its service to the new settlement. It had previously terminated at Fort McPherson.

The 1923 Voyage

In this year Lady Kindersley was able to repeat her journey as far east as Tree River. Captain O’Kelly, this time without his wife, was again senior HBC management representative on the voyage. It was a very tumultuous year in the Arctic. First was the problem with the distribution of supplies and gathering of fur returns that had not been accomplished because of the failure of the eastward leg of the supply voyage of 1922. This was eased somewhat by the arrival of the new motor schooner Aklavik which had been transported down the Mackenzie River for arctic service. Second there was the troubling matter of the double murders and subsequent trial and hanging.

Another matter that undoubtedly led to tension with HBC staff was the arrival of Phillip Godsell a special inspector for HBC fur commissioner Angus Brabant who was tasked with inspection of the Company’s arctic operations and business practices (that would eventually shake up their operations and lead to staff replacements). He joined the ship at Herschel Island and travelled with her to Tree River. Finally, although apparently not publicized at the time, there was the matter of executing a further eastward expansion of the Company’s trade to Victoria and King William Islands. This was the expedition lead by Pete Norberg on the schooner El Sueño that made the first ever west-to-east crossing of Queen Maud Gulf.

As reported in The Province newspaper of October 11, 1923, Lady Kindersley arrived in Prince Rupert on October 10. Here she landed a sailor suffering head and internal injuries from an accident aboard ship. On the in-bound leg the ship carried Leo Hansen (a Danish photographer) to Tree River on his way to join Knut Rasmussen’s expedition at Kent Peninsula. Outbound, she had conveyed missionary G.M. Merritt and his wife and a newborn son Edward. As noted earlier, the Merritts had been married on board the Lady Kindersley at Bernard Harbour in 1921. Other passengers on that leg included Bessie and Teddy Jacobsen (children of HBC employee Fred Jacobsen on their way to schooling in Vancouver under Captain Foellmer’s care) and Constable J.H. Bonsour from Tree River. The ship, also carrying a large cargo of fur, arrived safely in Vancouver on October 18, 1923 after completing more than 12,000 miles.

An interesting independent account of the voyage by the ships’ radio operator Reginald Harold Fricker may be found at page 44 of his personal story (RN Communications Branch Museum/Library website) The Ramblings of a “Matelot”. Fricker refers in this book to misfortune of the American power schooner Arctic (owned by H. Liebes and Co. of San Francisco), contracted by the Canadian government to take building supplies into the Canadian Arctic to establish a new RCMP post at Cambridge Bay. Instead she landed them at Baille Island as propeller damage sustained earlier at Point Barrow prevented her from proceeding. The police used the building supplies to establish a ‘temporary’ detachment at Baille Island while Lady Kindersley earned a windfall in forwarding the remaining supplies to the RCMP detachment at Tree River.

The 1924 Voyage

In response to a telegram sent to Fort Yukon in Alaska, inspector Godsell and district manager Herbert Hall set out to report to commissioner Angus Brabant at HBC headquarters in Winnipeg. The telegram had been brought to Herschel by RCMP Sergeant Thorne, the sad bearer of news of the confirmation and the date for the hanging sentence. HBC employees elected to follow basically the same route over the mountains to Fairbanks that the Klengenbergs had used in 1923, referred to later in this chapter. They arrived in Winnipeg on February19, 1924. Sadly, for Hall, who was popular in the Arctic and excelled in the field of winter travel and in establishing new posts, it was the end of his career with the HBC. His business practices, mainly over- stocking of inappropriate goods and over-extending credit revealed by Godsell’s investigations, lead to an ‘early retirement’ and his replacement by Tom O’Kelly. O’Kelly had been the senior HBC official on Godsell’s eastward inspection voyage on the Lady Kindersley in 1923, although Godsell conveniently omitted this fact in popular books he published long after the event. As reported by HBC manager Richard Bonnycastle (a subsequent district manager mentioned later) the replacement choice was very unpopular with post managers and O’Kelly’s tenure only lasted a little over a year.

In August 1924, HBC officials, members of the RCMP detachment and dozens of local trappers and traders on Herschel Island, awaited the arrival of Lady Kindersley bringing their annual supplies. Joining them were four members of the Canadian Corps of Signals who had journeyed down the Mackenzie River to install a powerful radio station on the island. At long last the Arctic would have instant and reliable communications with the outside world. Sadly, this was not to be, as Lady Kindersley became trapped in the pack ice near Point Barrow. She could not be freed and had to be abandoned. Fortunately, there were no casualties among the crew. The ships purser Percy Patmore, had managed to land near Point Barrow and organized land-based rescue efforts. On August 31, after weeks in the ice and repeated attempts to free the ship and transport the crew to safety, Captain Foellmer ordered the ship abandoned. The crew travelled over the ice and with the aid of canoes and an umiak (a type of open skin-hulled boat in use by the Inuit), reached the US Government vessel Boxer, then commanded by the HBC’s old friend Captain Whitland.

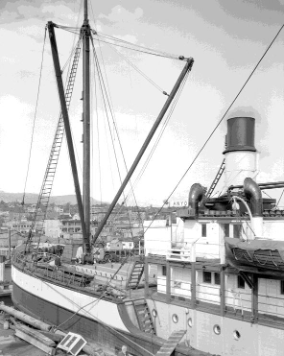

Shortly afterwards HBC’s steel steamship Baychimo, which had been rapidly dispatched from Vancouver, arrived and was able to transfer the survivors from the Boxer and transport them back to Vancouver. Baychimo had arrived at Vancouver from England via the Suez Canal only a few days before being sent to aid in the rescue. Before leaving she patrolled the edge of the ice for several days hoping to find and secure the Lady Kindersley to save at least part of her valuable cargo but all was lost, including the prized radio equipment. The Lady Kindersley was not the only vessel lost at Point Barrow that season. The H.Liebes and Company vessel Arctic, was abandoned on August 10, after being crushed in the ice. Only two vessels reached Herschel Island that summer, both American: Captain Klengenberg’s ship Maid of Orleans and Captain Pedersen’s ship the Nanuk.

She provided relief when Lady Kindersley was trapped in the ice and eventually lost. (Photo from Saltwater People Historical Society)

The year 1924 was significant, in that Canadian coastwise navigation rules—forbidding trade by foreign vessels—were evoked in the Arctic. No doubt this was done with some persuasion by the HBC. Heather Robertson stated, in her biography of HBC manager Richard Bonnycastle A Gentleman Adventurer The Arctic Diaries of Richard Bonnycastle, referring to loss of supplies carried by the Lady Kindersley:

“Unimpressed by the Company’s failure to fulfil its obligations to its Eskimo [sic] trappers, the police at Herschel Island were unsympathetic when the Company had Charlie Klengenberg banned from the Arctic coast because he was not a Canadian citizen.”

It is evident in Godsell’s report that the HBC was concerned by competition from American traders and were aware of Klengenberg’s voyage and trading plans in March 1924, which came about following a disastrous preceding year.

In 1923 Klengenberg and his family, located at Rymer Point, were in desperate straits because of the failure of H. Liebes and Company to delivery contracted and prepaid supplies and trading goods to them. He, together with his two sons, escaped the clutches of HBC’s arctic fur pricing by a hazardous winter trip over the mountains to Fairbanks, taking with him sample furs from those stored in a RCMP warehouse at Herschel Island. After Fairbanks, they travelled by railway to Seward, and then by steamer to Seattle. On arrival they sold the arctic-stored fur based on their samples and used the huge proceeds to purchase the motor schooner Maid of Orleans, hire a crew and equip her with supplies for his family and a large trading outfit. It would have been a brilliant move, but the implementation of the trading ban caught Klengenberg by surprise when his vessel arrived at Herschel Island in August. He was forced to winter at Herschel Island and suffered for a time as the main suspect in the overboard loss of RCMP Constable Ian MacDonald until it was deemed the man had likely accidentally slipped on the icy deck and fell into the arctic waters. Death would have come swiftly with little chance at calling for help or even being heard.

Fortunately, Captain Pedersen and his ship were on hand to relieve the 1924 situation, which action seems to have been precipitated by Canadian officials in reaction to Lady Kindersley’s predicament and the looming privations if she failed to reach her destination. Although Canadian newspaper stories failed to mention Nanuk’s participation and arrival at Herschel Island, Californian ones certainly did. One, the Santa Ana Register, in the October 10,1924 edition, quoted Captain Pedersen’s glowing account of supply relief and that the vessel had penetrated far into banned Canadian waters to do so.

The annual reports of the RCMP, usually full of Arctic information, do not seem to mention the wonderful service provided by Captain Pedersen in relieving this pending disaster. It must have been a source of embarrassment to them to contrast the welcome given to Captain Pedersen and that afforded to Captain Klengenberg.

The loss of the HBC vessel late in the season left the Company struggling to supply its far stretching line of posts. The new post at Cambridge Bay had to be closed because of lack of fuel but others received something through use of the Company vessels Fort McPherson and Aklavik as well as conscripted native schooners. After freeze up, a group of Company officials were forced to make a frigid dog team trek over the mountains to Fairbanks Alaska to gain telegraphic access to communicate with the Company and to make the railroad connection in order to travel back to Vancouver. Most proceeded on the railway but E.J. ‘Scotty’ Gall, then a HBC apprentice, and Ambrose Agnavigak a former member of Stefansson’s Canadian Arctic Expedition (CAE), returned to Herschel with cash, vital supplies and fur trading prices and Company instructions to enable trading to continue. In his retirement years, Gall, a raconteur of much insight, was pursued by famous authors and historians for stories of his vast experience in the arctic.

The Baychimo Years 1925 – 1931

Godsell’s inspection report, published in March 1924, included a recommendation that the Lady Kindersley be replaced by a fully powered vessel (as opposed to an auxiliary powered vessel) to take advantage of the limited time given for arctic navigation east of Herschel Island. The happenstance of the loss of Lady Kindersley and the availability of the Baychimo for the 1925 season provided an early satisfaction of this recommendation.

The replacement under Captain Sydney A. Cornwell was the Baychimo. She was a 230-foot, steel-hulled steamer, built in Gothenburg Sweden in 1915 and purchased by the HBC in 1920, registered with London as her home port. Originally employed in the Company’s eastern arctic trade, she had been used from 1922 to 1924 in new fur trading venture the Company started in Kamchatka Siberia. Her subsequent summer employment for western Arctic service was timely, as relations with the Soviet government had broken down and needed permissions for this trade were not forthcoming.

Baychimo was the largest and first steel vessel to enter the treacherous ice infested waters of the western Arctic. Many ‘beach scoffers’ predicted failure of a steel hull in such conditions.

Although owned by HBC, she was registered in London and, as such, was operated primarily as a ‘British’ ship with a ‘British’ crew. When cargoes could be found, winters were spent transporting them to and from Britain-usually ending up at Ardrossan in Scotland for necessary maintenance.

As documented in Anthony Dalton’s well-researched and readable book Baychimo: Arctic Ghost Ship, she completed seven outbound voyages from Vancouver but unfortunately only six return ones. In 1931, she became trapped in the ice, was abandoned, and the derelict vessel became a ‘ghost ship’. Prior to this tragedy, Baychimo courageously delivered cargoes and personnel to the western Arctic through the shallow and poorly chartered waters, while often facing violent summer storms and fogs. She bounced between—and over—shallow reefs, threading her way through ice flows to bring sustenance to the Arctic and to take out the fur returns. Her crew became very efficient at temporarily ‘lightening’ ship and ‘heaving-off’, through the use of her powerful steam winches and heavy anchors.

In the process she suffered dents and damage to her hull and the loss of propeller blades – which brought work to Vancouver and other shipyards. The eastern limit of her voyages was usually Cambridge Bay on Victoria Island, although in 1928 she went as far as Flagstaff Island southwest of there. In her time, tiny flimsy buildings were replaced by more substantial weather- tight structures and trading posts were established southward into Bathurst Inlet.

(City of Vancouver Archives – AM 1506-53-2, CVA-447-1987)

The 1925 Voyage

Her initial voyage in 1925 was a very busy one, particularly since the Arctic had received inadequate supply in 1924 because of the loss of the Lady Kindersley. This was the first time that a large supply ship ever reached Cambridge Bay, consisting only of a vacant hut and serving as an outpost for the Kent Peninsula post. She left supplies there to be forwarded to King William Island by the Fort McPherson, which had not yet returned from her first trip to that island. That summer Baychimo carried many prominent passengers intent on getting first-hand information on the Arctic. They included HBC fur commissioner Angus Brabant, Inspector Hugh Conn and Marine Superintendant Captain Mack.

In a HBC company interview (part of a series on Company employees Accession HB 1944/15 held at the HBC Winnipeg archives), Scotty Gall indicated Captain Mack had been involved in sounding a channel into Tuktoyaktuk, so it seems clear that the Company was already looking at alternatives to the Point Barrow route at that time. Also, on board were replacement HBC staff such as Ray Ross for the Tree River Post, Canadian government investigator Major L.T. Burwash bound for King William Island and former Anglican missionary Hoare for Tree River who was there to start wildlife investigations for the government. Her eastern trip through Coronation Gulf, Dolphin and Union Strait and Amundsen Gulf and return to Herschel Island seems to have been made without serious incident. However, from there, prior to her demise in 1931, it proved to be the one in which she had the greatest difficulty in exiting the Canadian Arctic. With preparation already in hand for wintering at Herschel Island, she was able—at the last possible moment—to escape. As final freeze-up was occurring, she arrived at Point Barrow on Oct 2, a full four weeks later than planned. After returning to Vancouver, Baychimo proceeded to Britain via the Panama Canal with a grain cargo for Devonport. Afterwards she proceeded to Ardrossan, her usual Scottish base, for repairs and discharge of the crew.

At Aklavik the Royal Canadian Corps of Signals opened the Arctic’s first radio station, the one originally planned for Herschel Island. The All Saints Anglican Hospital was built and a Roman Catholic mission and hospital was also established. The HBC facility became a full post and was moved across the river to the main part of the settlement.

The 1926 Voyage

The voyage to the Arctic in 1926, which reached Cambridge Bay, was made without serious difficulties. At Tree River Baychimo was successful in freeing sister Company ship Baymaud from a grounding that had held her captive for several days. Baychimo returned to Britain with a lumber cargo that fall. The annual report of the RCMP noted the establishment of a new detachment at Bernard Harbour and the relocation of the Tree River detachment to Cambridge Bay. It is reported that the HBC carried supplies for the RCMP that summer and it is evident she and other HBC vessels must have been used for the establishment and relocations of the detachments.

The 1927 Voyage

The 1927 RCMP report reinforced the previous 1926 one, that new police detachments were established at both Bernard Harbour and Cambridge Bay, the latter mainly with materials from the post at Tree River, which had been closed. Ian McKinnon became the HBC post manager at Cambridge Bay in 1927 where new buildings were being erected. The location became the key fur trade centre in the central arctic under a new government policy that centralized competing posts away from animal migration routes. The closing and transfer of the Kent Peninsula post to Cambridge Bay and the establishment of a post in Bathurst Inlet in 1927 ensured a busy year for Baychimo in 1927.

Important cargo delivered to the eastern expanding fur trade included new distribution schooners Polar Bear that unloaded at Tree Island and Blue Fox that probably unloaded at Cambridge Bay, a new Anglican mission house for Cambridge Bay, a new eight-ton engine for the venerable Fort McPherson (also at Cambridge Bay) and material for a new post in Bathurst Inlet that was to be established by HBC Chief Inspector Hugh Conn. The two new vessels were likely the two 41-foot centerboard schooners reported to have been constructed by Eriksen Shipyard in North Vancouver for the HBC for shipment as deck cargo as reported on page 222 of the May issue of Harbour and Shipping. Anecdotally, they appear to have not been registered, at least not in the Vancouver registry, as their function was likely to assist in local distribution as the Baymaud was to be retired from active service. Baymaud was tied-up at Cambridge Bay to serve as a floating warehouse and workshop prior to the departure of her crew on the Baychimo on her return trip that year.

Conn also had an additional assignment following completion of his inspection post expansion duties. That winter he was to reconnoitre a possible trade route from the western Arctic through to Wager Inlet on Hudson Bay. A article in The Province of July 20,1927 announced that Consolidated Mining and Smelting Co. geologist Donald C. McKechnie would sail on the Baychimo and meet Conn at Herschel Island and “—travel with him by canoe and dog train across the hinterland of Canada as far as Hudson Bay”. To facilitate the mission, Baychimo brought Hugh Conn’s special eight-dog team from Vancouver for the expedition. It is not clear if McKechnie completed the trip but Conn certainly did. Bishop Isaac Stringer and his wife travelled with the ship from the Mackenzie Delta to Cambridge Bay, where he oversaw the erection of the new mission house for the community, observed the new police detachment and the hoisting of the new engine into the Fort McPherson. After leaving Cambridge Bay on the homeward journey, a new post was finally established in Bathurst Inlet to Conn’s satisfaction after one false start. While Captain Sydney A. Cornwell and some other crew members returned to Britain for the winter, the ship and several officers stayed with the ship at Esquimalt, where major repairs were undertaken at the Yarrows shipyard.

The 1928 Voyage

After his marathon winter trip Inspector Conn returned to the arctic in 1928 to continue his investigation into the sorry financial state of Company affairs that persisted after Godsell’s earlier 1925 inspection. He travelled down the Mackenzie River accompanied by Richard Bonnycastle, a recent Oxford University graduate who had joined the Company seeking adventure, and who would accompany Conn on his travels to HBC posts on the Baychimo that summer. Bonnycastle started that year as an accountant and would become the district manager for the western Arctic in 1929, a position he held until 1933.

When Baychimo reached the mouth of the Coppermine River, Bonnycastle noted in his journal that a new store surrounded by tents had been erected marking the establishment of a new permanent community that he referred to as Fort Hearne (often confused with the neighbouring post of Cape Krusenstern, closed in 1929). It was later known simply as Coppermine before its present name Kugluktuk came into prominence. At Wilmont Island he noted they left off “the trapper-trader Patsy Klengenberg and Ikey Bolt with their outfit”. The implication that “their outfit” had been transported by the HBC reflected the increasing cooperation between the HBC and the Klengenberg fur trade family after Christian Klengenberg’s retirement and the sale of his schooner Old Maid No.2 to the Company in 1928. The relationship previously had been—to say the least—very competitive. A related matter to this was Baychimo’s rescue of Patsy and Ikey Klengenberg and a small child when the Baychimo’s crew later found them and their vessel the Doctor Rymer shipwrecked on a small island west of Wilmont Island. They had been the victims of a huge storm that had delayed the Baychimo at Cambridge Bay and was responsible for wrecking several schooners at Baille Island.

The Baychimo carried building materials to complete the consolidation of HBC posts in the Coronation Gulf in accordance with new government regulations. The materials included building supplies for expanding the warehouse at Cambridge Bay. After leaving that post she traveled 120 miles southeast to Flagstaff Island near the mouth of the Perry River. This marked the farthest eastward destination she would ever reach. Here, as recorded by the Ottawa-based government official Hon. Frank Oliver in an article published in the March 2, 1929 edition of the newspaper Calgary Herald, she anchored and some of the crew discharged freight for the new King William post onto the Fort McPherson. Other crewmen, to Conn’s chagrin over its forced removal by the government, travelled 10 miles by launch to the recently installed Perry Post, which was then disassembled and abandoned. Before making a final visit to Baille Island, where storm damage was previously noted, Baychimo called at the five-year-old Fort Harmon at the head of Albert Sound and took down and brought aboard all the post buildings. She then proceeded to the north mouth of the sound where they were re-erected at the new post of Walker Bay, that came to be known as Fort Collinson..

Other significant events of the year included a return of government investigator Burwash who travelled along the arctic coast in the government schooner Ptarmigan and wintered at Gjoa Haven on King William Island. In the winter he visited the HBC schooner Fort James which had entered the western arctic from St. John’s Newfoundland and was wintering at Oscar Bay on the Boothia Peninsula east of King William Island. Practical attempts to find better means of supplying the fur trade in the central Arctic and to evaluate fur trapping possibilities east of King William Island, described long after the event in an article in the September 1936 issue of Beaver magazine by W.E. Brown included the eastern schooner’s visit and a trial tractor expedition from Wager Inlet on Hudson Bay The year also marked the entrance of the RCMP’s St. Roch into arctic service.

Baychimo experienced little difficulty in returning to Vancouver from Herschel Island that fall. She was able to obtain a wheat cargo and proceeded to Britain for the winter.

The 1929 Voyage

Baychimo’s business was expanded in 1929 as a mining prospecting boom had sprung up in the Arctic. It was centered around the new community of Coppermine and Bathurst Inlet. At Coppermine building supplies were landed for completion of fur trading facilities, mission buildings for both the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches, the construction of a medical clinic, and huts for the exploration companies. At Burnside River materials were landed for a base for Dominion Explorers. Winter provisions, fur trading outfits, coal and liquid fuels, including a huge amount of aviation fuel for caches in the district, made up record cargos that were carried by HBC ships that season.

The rapid mineral investigation that ensued over a vast and inaccessible area was only possible by the use of a new tool—the bush plane—which had never been seen in this area before. In winter, ski-equipped, it could land on the frozen tundra while in summer, float-equipped, on the innumerable lakes of the region, taking prospectors and supplies rapidly to potential areas of mineralization. The prospecting companies included North American Mineral Exploration Company (NAME), Dominion Explorers and the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company.

Baychimo’s cargo for NAME even included a set of floats for one of its aircraft allowing it to be changed from winter to summer flying in the north avoiding the time-consuming diversion to a southern base to perform the conversion. Dominion Explorers chartered the HBC schooner Polar Bear to support its operation in Bathurst Inlet that year.

(Library and Archives Canada MIKAN 3393549)

On August 31, only 5 days after Baychimo had sailed eastwards, HBC Coppermine post manager Barnes noted in his journal the first arrival of aircraft in the western Arctic. They consisted of two NAME aircraft, each with three occupants. He also duly indicated that the celebration of the important event took a terrible hit on his permit (annual allowance of alcohol – usually 12 bottles). Later that year two aircraft, belonging to Dominion Explorers, carried the MacAlpine Party, who were attempting a pioneering flight from Hudson Bay to Bathurst Inlet but became lost and had to land near Dease Point in Coronation Gulf after they ran out of fuel.

Their crews and passengers, consisting of eight persons in total, eventually turned up at Cambridge Bay after safely crossing Coronation Gulf with the help of local Inuit after freeze-up. In the meantime their disappearance precipitated the arctic’s first major air search, at the time reported to have cost the staggering sum of nearly $400,000.

Another significant event in 1929 was the arrival of the HBC motor schooner Fort James at Gjoa Haven on August 28, 1929. The vessel, which had left St John’s in 1928 and wintered at Oscar Bay on the Boothia Peninsula, had duplicated Amundsen’s journey to this remote location through Lancaster and Peel Sounds. Fort James’ accomplishment finally marked HBC’s long dreamed-of conquest of the Northwest Passage by their vessels. That year the Baychimo had made the western segment from Vancouver arriving at Cambridge Bay in late August. The Fort McPherson, which had waited 14 valuable days at Cambridge Bay for the Fort James to bring out the King William Island fur returns for shipment on the Baychimo, finally, in desperation, made a dash to obtain the fur, arriving at Gjoa Haven on August 23. After leaving supplies for Fort James, she quickly returned to Cambridge Bay so that the valuable cargo could be shipped out on the Baychimo on the 1st of September.

The Fort James arrived at Gjoa Haven on August 28, and after picking up the supplies left for her, made a “bluff attempt” to reach Cambridge Bay. The “bluff attempt” description was recorded in the diary of Cecile E. Bradbury, senior HBC fur trader on the vessel, and represented the crew’s frustration with their captain whose main objective seems to have been the avoidance of another winter in the Arctic. Fearing the loom of ice, her captain retreated and proceeded to attempt a homeward voyage to Newfoundland. When this too met in failure, because of blocking ice, Fort James returned to Gjoa Haven, arriving on September 21, only seven hours after the Fort McPherson had departed from her second trip to the King William Island after bringing in the ‘winter trade outfit’ (trading supplies for the season).

In a missed opportunity to acknowledge a truly marvellous achievement, the headline that begged to go out on the occasion of the Fort James’ arrival at one of the most remote places on the inhabited earth was that two Canadian-built and registered vessels, one from each coast, had finally achieved the Northwest Passage and furthermore, that the three vessels working together had achieved it in just two years. Instead, the cautious, closed-mouthed Company hesitated, perhaps hoping for the more complete result of the Fort James’ arrival at Cambridge Bay (her intended destination), or even better, her return to her home in St John’s. In the delay, the epic accomplishment was further overwhelmed by headlines reporting on the missing MacAlpine party.

An erroneous story of the accomplishment, supplied by an unknown source did appear in the Calgary Herald on October 24, 1929 announcing fur brought back by the Fort James had been delivered to London. The article was accompanied by a fanciful map showing Fort James’ route through Bellot Strait to the Gulf of Boothia and then by Fury and Hecla Strait to Foxe Basin in Hudson Bay.

The lead article in the Company-based version of events, shared with news of the MacAlpine expedition, finally appeared in the Montreal Gazette of November 7, 1929.

Some years after the event, HBC district manager W.E.Brown (from the September 1936

Beaver article previously mentioned), made this remark about the publicity given the event:

“The feat was the bridging of the Northwest Passage, and, being given little publicity at the time, the event passed almost unnoticed.”

As a final comment on this rather bizarre story, it is utterly amazing that Fort James’ captain, upon reaching Gjoa Haven, refused to proceed on to Cambridge Bay where his winter supplies were waiting for him; this given that Fort McPherson had left only hours before his arrival and had an easy return voyage. The only possible logical explanation was that Captain Bush was under orders to position his vessel at this location with its powerful radio sets to assist in the MacAlpine party search, but this does not seem to have been communicated to the crew and no mention seems to have been made of such in the literature. As it turned out, the news of the party’s recovery was relayed over Fort James’ radio set, while the crew, short on supplies, passed a very uncomfortable winter.

Another important event for the people of the arctic that year was the opening of a residential school for Inuit and other children in the HBC’s old post facilities at Shingle Point by the Anglican Church. This action had been prompted by native leaders from the Mackenzie Delta and the western Arctic to enable their children to obtain education closer to their homes. Short of sending their children by ship to Vancouver, as mentioned for the Jacobsen children, the nearest option was the residential school at Hay River that served primarily Dene children.

Baychimo seems to have had little trouble in following her itinerary in 1929 including landing materials for Dominion Explorers in Bathurst Inlet. She arrived back in Vancouver on Sept 25. Travelling aboard were Christian Klengenberg’s daughter Etna and her husband Ikey Bolt. Etna was in Vancouver to stay with her father while recovering from pleurisy. Baychimo spent the winter under ‘orders’ as no winter cargo appears to have been found for her.

1930 Voyage

Ikey and Etna Bolt returned to their home via the Baychimo on her inbound journey. At Herschel Island she picked up a number of passengers including Reverend Webster and special arctic investigator Richard Finnie.

Although the 1930 voyage was successfully completed by Baychimo, it was a sad one for her in one respect: She had been cleared to try for the Northwest Passage if conditions proved favourable. Indeed,at least pertaining to ice conditions, the Fort James had been able to return to the east without incident from the Company’s post on King William Island. However early in the season, the ice gods of Point Barrow threw a wrench in these plans: During the annual race around this headland, which was ‘won’ by the RCMP’s St. Roch, the HBC vessel lost several propeller blades which caused her to limp through the remainder of the voyage.

The risk to continue through the passage in such condition, where there was no support for hundreds of miles, was far too great and Captain Cornwell reluctantly returned by the usual route. With that one decision, Baychimo lost her single opportunity of gaining the laurels of being the first ship through the passage west-to-east in a single season, the first ship to circumnavigate North America, and the first ship to circumnavigate the world through the Northwest Passage. That year, even in her dilapidated condition, she was successful in heaving St. Roch off a reef near Cambridge Bay. Observers stated that without Baychimo’s assistance, the grounding would have ended the police ship’s career. Demonstrated time and again in the stories from the arctic, survival and success rendered down to a matter of timing and outright sheer luck. That Baychimo could have taken these arctic ‘firsts’ instead of St. Roch‘s crew, who ultimately claimed these honours, is yet another example of the role that chance plays in that harsh and unforgiving environment.

The final chapter of the Fort James’ Northwest Passage saga played out in 1930. As recorded in Bradbury’s personal diary on August 5, 1930, the Fort McPherson, 4,800 miles from her building yard in Vancouver pulled alongside the Fort James, 3,500 miles from hers in Shelburne Nova Scotia, and transferred supplies needed for the Fort James’ homeward journey. She left on August 7 and arrived, without serious incident, at St. John’s on September 12, 1930, completing the first ever east-to west crossing of this section of the Northwest Passage; and if the other ships involved were included, the first ever east-to-west crossing of the Passage.

These are the words of Henry Lyall Ross Smyth, Fort James’ young radio operator, historian and photographer, in an essay he wrote for his studies at McGill University (part of the collection of the Library and Archives Canada):

“September 12th 1930, we arrived St John’s Newfoundland, having safely completed a voyage to the Western Arctic, during this expedition we met ships entering the Arctic from the Pacific Ocean, thus linking the Pacific with the Atlantic through the Northwest Passage, which had been the goal of mariners.”

Again sadly, particularly for employees who were responsible for the accomplishment, the staunch old Company’s press announcement was muted, if non-existing, and their long-sought goal remained unheralded. Perhaps it was too much for the present managers to confront the ancient dreams of their ancestors with the thought that the Company’s greatest achievement with respect to the Northwest Passage was in the wrong direction. In contemplation it would be fun to contrast the thought of what publicity may have ensued, if one of the several twentieth century adventures bent on the west-to-east passage had pulled it off first. What if it had been Stefansson? As events played out, he was only able to hold what Fort James had achieved as a forgotten dream!

Fort McPherson was not so lucky in reaching a home in 1930. On October 3, after her third trip to King William Island, the indefatigable vessel was wrecked in a gale on her way to winter quarters at Bernard Harbour off Richardson Island in Coronation Gulf. Fortunately, there was no loss of life and only a little of cargo. The crew consisting of Captain D.O. Morris and Engineer Otto Torrington were both rescued. Perhaps fittingly, the location of her bones lies only about one hundred miles to the east of those of her arctic companion Fort James, crushed in the ice and lost in 1937.

A significant visitor to the arctic in 1930 was Richard Finnie. That year, he travelled with Major L.T. Burwash on parts of the government investigator’s third trip to the arctic. Finnie was on special assignment, with typewriter and both still- and movie-cameras, to document arctic conditions. Finnie’s travels on the Baychimo, other arctic vessels, on aircraft and by dog team, together with his descriptions of events and characters, are delightfully narrated in his book Lure of the North. For his arctic adventures he took up residence at Coppermine in the building housing the radio station that was installed soon after his arrival.

Later he was a huge help to a selfless arctic hero Dr Russel Martin, a young Scot, who had come to Coppermine the previous year to operate the first medical station in the western arctic. In 1929, the year that the medical station had been opened by Dr. Martin, convicted murderer Uluksuk (or Uloqsaq) had been returned to the community on the Baychimo after serving his sentence. Tragically for the community, he was badly infected with tuberculosis and an epidemic soon spread throughout the community and adjoining countryside. Finnie’s photographic work was used in the National Film Board movie Coppermine that documented the short but heroic work of Dr. Martin in trying to combat the spread of this terrible disease. When Martin travelled to Ottawa to beg for desperately needed help in dealing with the epidemic, he was told his services were no longer required. He was forced to return to Scotland.

(Library and Archives Canada MIKAN 3388944)

The RCMP made a change in an arctic detachment that year. Because of storm damage sustained in 1928 and 1929 Baillie Island was gradually being washed away jeopardizing their facilities. As a result, they closed their detachment at that location on August 6 and relocated it to Pearce Point where there was a safe harbour for small ships. As for the Baychimo, Captain Cornwell and officers stayed in Vancouver over the winter 1930 -1931 as the ship need work on stern.

The 1931 Voyage

In 1931, because of ice conditions experienced on the inbound journey to Herschel Island, it was decided that Baychimo would only proceed to Coppermine. The decision was made after consultations between Captain Cornwell and fur commissioner Ralph Parsons, district manager Richard Bonnycastle and other Company officials who awaited the ship at Herschel Island. But shortly after leaving Herschel with persisting poor ice conditions, Captain Cornwell had second thoughts and came to the conclusion he should return to Herschel Island, land all his cargo and immediately head to Point Barrow. However, he was convinced by Parsons that they should stick to their plan, “Egged him on without taking any responsibility.” as Bonnycastle put it, and they pressed on to Coppermine. As events played out, he should have followed his own intuitions.

On her homeward voyage, loaded with fur and other freight and carrying HBC employees, Baychimo’s service to the fur trade came to an end. Although she had run the 400-mile gauntlet from Herschel Island and made it past Point Barrow, she found it impossible to proceed south. The strange tale of her fate is told in detail in Dalton’s book. In brief, she was held in the ice without hope of release. The crew and passengers transferred ashore, building a winter structure out of hatch covers, hold-lining lumber and canvas. Baychimo broke free of her anchorage overnight in a storm to become a ‘ghost ship’ and was sighted for many years after this event, and even on occasion boarded by local residents, who recovered most of her fur cargo. The Arctic holds her secrets firmly: Baychimo’s final fate remains unknown., Interestingly, the person who recovered the greater part of her fur cargo was O.D. Morris who was onboard for what turned out to be her final voyage. He is remembered as the last captain of Fort McPherson.

The use of radio provided for rapid rescue for passengers and some members of her crew. After quickly obtaining permission from head office, district manager Richard Bonnycastle organized an airlift by local bush pilots for the evacuation. Lucky passengers and crew members, partially selected by lottery, were flown by wheel-equipped aircraft from a frozen lagoon located near their make-shift wintering location to Nome Alaska. At Nome they were able to board the last steamer of the season to Seattle.

The Victoria reached Seattle on November 2. Carrying the annual fur trade records, Bonnycastle and his accountant J.O. Kimpton, were back to Company headquarters in Winnipeg on Nov 5 to report the mishap to management. In March 1932, the remaining 14 members of the crew who had stayed behind at the winter enclosure, including Captain Cornwell, were finally evacuated by air and by steamer. At this point all hope of locating and boarding the missing vessel had been lost. Bonnycastle’s article published in the March1936 Beaver magazine provides further details of the ordeal.

Other Ships in the Baychimo Years 1925 – 1931

During the Baychimo-era the HBC sent two other ships to trade into the arctic. The first was the Baymaud, formerly owned by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen as the Maud. The HBC’s fur trade commissioner authorized her purchase after Amundsen’s ‘arctic drift’ experiment went bankrupt. The vessel had already completed the Northeast, Passage, and finally after a further three years without further progress, popped out of the ice near Nome. In 1926 after purchase and Canadian registration the HBC sent the vessel north with a fur trade cargo under Captain Gus Foellmer. It was intended that she be used for local transport and, when Baychimo was present, to act as ‘pilot’ vessel. Scotty Gall, a veteran of the arctic, strongly pronounced her unsuitable. Not only did Gall complain that her confined holds, laced with ice pressure bracing, impeded stowage and removal of cargo, she required a full engine room crew for operation.

Underpowered, she could barely sustain 5 knots, barely enough to maintain steerage and headway against arctic currents. Considered ‘stellar’ in some accounts, the words of experienced arctic ice-masters say it best: Scotty Gall referred to her simply as “a lemon” which succinctly summed up her unworthiness for arctic duty.

She was used in the summers of 1926 and 1927 to establish new posts at Ellice River and Perry River and to move buildings from the Kent Peninsula to Cambridge Bay. In the fall of 1927 her crew, with the exception of her radio operator Terry Crisp and her carpenter, took passage for Vancouver on the Baychimo after she was tied up opposite the Company post at Cambridge Bay for the intended purpose as use as a floating warehouse and machine shop. This assignment also did not work out for her as she began leaking badly through her stuffing gland and required constant pumping to keep her afloat. Eventually she was heaved up on the shore, and listing, she became one of Cambridge’s Bay chief landmarks. Recently, ownership of the vessel has been returned to a Norwegian historical group who have raised her and returned her to Norway. While not particularly successful for freight transportation, the Baymaud did possess a powerful radio transmitter-receiver set that provided the Company with direct and instant communication to the arctic – a tremendous benefit. In 1929 the radio was used in providing communications during the aerial search and recovery of the lost MacAlpine expedition as well as in the planning and delivery of relief supplies to HBC’s eastern schooner Fort James that was wintering at Gjoa Haven on King William Island.

The second vessel was the Old Maid No. 2, which HBC fur trade commissioner C.H. French had personally purchased from Captain Christian Klengenberg in 1928, when Klengenberg retired from the Arctic. French later resold her to the HBC. Under Klengenberg, the vessel had already made two trips to the arctic. The first was under American registry as the Maid of Orleans from 1924 – 1925 when she was forced to winter at Herschel Island, and secondly under Canadian registry as Old Maid No. 2 in 1926.

During the winter of 1924-1925 Klengenberg is reported to have made another awe-inspiring trip over the mountains. Although details are lacking of how it was accomplished, he was able, after applying for naturalization, to sort his problems with Ottawa and obtained the release of his ship and goods to continue trading in the Arctic. Later, after returning with his ship to the pacific coast in the fall of 1925, he was successful in winning compensation in a San Francisco court against H. Liebes and Co. for their failure to deliver the goods he had previously ordered. Under HBC ownership, she made two trips to the Arctic, in 1929 under sealing Captain W.H. Gillen and again in 1930 under F.L. Coe, former mate of the Baychimo.

Notorious from her early years as a south pacific slave trader, and under Klengenberg’s command in 1924 during the mysterious disappearance of RCMP Constable Ian MacDonald , she continued her infamy in 1929 when Captain Gillen was found dead floating amongst pilings near her berth in North Vancouver. Gillen, an experienced navigator, had piloted both Canalaska’s new motor schooner the Nigalik and the RCMP’s St. Roch to the arctic, respectively in 1926 and 1928. In 1931 HBC sold the vessel to Paul Pane of San Francisco who used her in the rum-running trade.

The Final Years 1932 – 1933

After Baychimo’s demise, two further attempts were made to supply the arctic fur trade from Vancouver. The first was successful but the second was not. In 1932 the Company arranged a bare-boat rental of the 149-foot Danish motor vessel Karise from the Seattle-based fur trading company Swenson Fur and Trading Company to undertake the arctic voyage. She was originally built in Thuro Denmark in 1918 as the Svendorgsund for ice service. She was purchased in 1930 by Swenson in Copenhagen to replace their lost vessel Elsif and renamed Karise. The vessel had been used by Swenson in their Siberian trade.

Her voyage to the Canadian arctic was made under Captain John Murray, an experienced HBC master from the Company’s eastern arctic trade, whose command prior to retirement had been the Nascopie. The first officer for Karise’s voyage was R.J. Summers who had served on the Baychimo. In spite of a broken-down compressor and a resultant lack of compressed air for starting the engine, the ship successfully completed a voyage to Coppermine and Fort Collinson before returning to Vancouver on September 25. She brought back seven HBC officials including district manager Richard Bonnycastle, who was finally able to complete the north pacific voyage without interruption, and versatile company carpenter George McLeod who completed several tasks in the arctic including the repair of the Aklavik. The chartered vessel was returned to her Seattle owners on September 27, 1932 and her master and mate returned to their homes in England.

She was sold to Soviet interests in 1933 and renamed the Soyuzpushina. In 1934, she was the first vessel to leave the United States under the Soviet hammer and sickle flag, taking a cargo of salt from San Francisco to Vladivostok.

The well-known locally-based vessel Anyox under Captain B.D. Johnston was chartered to make the 1933 arctic voyage with a huge supply cargo intended for both the HBC and the RCMP. Under the supervision of HBC’s Percy Patmore and R.J. Summers as first officer, she sailed from Vancouver on July 6. It was a very difficult ice year, and when encountering the pack ice near Point Barrow, she damaged her bow and began leaking so badly she was in danger of sinking. The flow was stemmed somewhat when her crew were able to put a temporary timber and canvas patch in place.

They were assisted in the later stages of this exercise by the crew of the United States Coast Guard cutter Northland, whose crew came to her aid in response to her distress calls, arriving on July 28. After the cutter had cut a path to her and assisted her out of the entrapping ice, it was determined that in her now fragile condition, she could not continue the voyage. She was forced to turn south to Unalaska where further repairs were affected so she could return safely return to Vancouver. She arrived there on August 24 while the USCG Northland returned to her base at Nome. Meanwhile the indomitable Captain Pedersen, whose ship the Patterson had been trapped in the ice slightly north of Anyox, succeeded in blasting himself free with dynamite.

Mindful of the loss of the Lady Kindersley in 1924 and the huge difficulties in arctic supply that ensued and the increased needs of 1933, HBC’s supply system went into emergency mode. In spite of difficulties occasioned by high water on the Mackenzie River, that damaged warehouses and dock facilities including the loss of wood piles that fired their river steamers, they were able to respond effectively. Unlike previous emergencies, in 1933 they had modern radio communications that enabled them to plan and execute the delivery of replacement supplies and arrange for forwarding them all over the western Arctic.

The Company’s river steamer Distributor arrived at Aklavik on August 31 pushing a huge barge loaded with 700 tons of goods. The remaining problem of further forwarding goods before freeze-up—for a company nearly devoid of distribution vessels—was solved by the cooperation and mobilization of dozens of local concerned citizens in an action akin to the miraculous evacuation of Dunkirk that occurred in the early stages of WWII.

Waiting at Aklavik was a fleet of dozens of motor schooners chartered by the Company for the purpose of distributing supplies and owned by the prosperous Inuit and white trappers engaged in the fur trade. Some, like the Anna Olga, had been brought to the Arctic under their own power (bound for Fort Collinson) while others had been brought in as deck cargo on supply ships, but many of them, like the Sea Queen (she was headed for Baillie Island) had been constructed by Edmonton boat-builders, transported to Waterways by rail and then sailed down the Slave and Mackenzie rivers to the Arctic.

The vessels quickly loaded from the barge and dispersed throughout the area; some taking supplies to the school at Shingle Point while about twenty hurried to Herschel Island where the St. Roch was waiting to take on some of their loads for a unscheduled trip to Cambridge Bay. A few of the larger vessels ventured as far as Fort Collinson in the Coronation Gulf and one even farther to Bathurst Inlet to resupply fur trading posts. From this grand effort, the arctic had been supplied but it also marked the last year for any further attempts to supply out of Vancouver.

Aftermath

In 1934 HBC abandoned ocean supply and switched the supply route for the arctic fur trade to its Mackenzie River system. With a reliable railhead at Waterways, substantial improvements at Smith Portage and the introduction of powerful diesel low-draft tugs like the Pelly Lake that could traverse the Mackenzie Delta, this alternative became competitive and compelling. Of greater importance, it avoided the risks of the Point Barrow route. Accordingly, the long- anticipated new port of Tuktoyaktuk was finally established. It was located a few miles east of the eastern side of the Mackenzie Delta, where cargo from the river system could be received and forwarded by arctic distribution vessels. A new distribution vessel, Margaret A, was acquired and the HBC schooner Fort James was transferred from the east coast via the Panama Canal to assist Aklavik in the onward distribution along the arctic coast.

(Hudson’s bay Company Archives, Archives of Manitoba. 1987/363-F-85/126 “Fort James

seaworthy again and ready for action. “Photographer. R.N. Hourde, 1936.)

After 1925, HBC had moved its headquarters from Herschel Island to Aklavik when radio communications were established there. However, they continued to maintain a store at Herschel Island until 1937. Eventually all its facilities were removed, and no evidence of their presence exists today. Captain Pedersen’s last voyage to Herschell Island was made on the Patterson in 1935 but in 1936 he had all supplies for his Canalaska division shipped by the HBC down the Mackenzie River. In 1937 all his remaining assets, including his store and warehouse on Herschel Island and trading posts at Cambridge Bay, Bathurst Inlet and Gjoa Haven and the venerable motor schooner Nigalik were sold to the HBC and integrated into their system.

The RCMP transferred its sub-district headquarters to Aklavik in 1931 but maintained a presence on Herschel Island until it permanently closed the detachment in 1964. Their buildings, including the infamous ‘bone house’, remain at Herschel Island as part of Herschel Island – Qikiqtaruk Territorial Park operated by the Yukon Territory.

Although HBC ended up with a dominant near-monopoly position in the western Arctic trade at the end of the Vancouver supply period, the venture from a profit prospective appears to be far from successful. Although not a matter of specific research for this article, this message stands out from the review of documents cited, particularly those related to Philip Godsell and Richard Bonnycastle. In an interview conducted by the Northwest Territories Archives after his retirement, Scotty Gall remarked to Richard Valpy (Recording N-1988-040-001,37:30), he felt that the Company did not turn consistent profits from its western arctic trade until after World War II and when a welfare system had been introduced.

Conclusion

Vancouver has for years had a close connection to the western arctic and its related Northwest Passage. Anyone who has visited the Vancouver Maritime Museum cannot escape this fact.

However, what is less apparent, is that this connection goes back much earlier than the St. Roch’s arrival in the arctic in 1928.

Following in the wake of whalers and other fur traders, the HBC established itself at Herschel Island in 1915, then reached eastward through the ice-plagued Dolphin and Union Strait into the central arctic in the Coronation Gulf and Queen Maud Gulf areas, gradually expanding and ultimately dominating the trade. Police detachments and missionary posts, and even a medical station, followed the establishment of fur trading posts which in turn, enabled the foundation of permanent settlements along the liveable portion of the Northwest Passage. The supply of this enterprise from Vancouver from 1914 until 1932, utilizing an array of charter and Company- owned ships, stands as a remarkable achievement of logistics, seamanship and luck. In spite of the loss of two Vancouver ships and the venerable Fort McPherson, no lives were lost.

As a final thought, the author likes to contemplate the motor schooner Fort James in 1930 homeward bound to St. Johns Newfoundland on her epic journey from Gjoa Haven through Peel Sound, under an anxious Captain Bush. Her engine fueled with diesel from a Vancouver dealer and her crew fed with meals cooked using BC coal, hers had not been another expedition to find the remains of Franklin – she had come to this most remote location to find a possible alternative commercial supply route and to seek out the lucrative fur of the arctic fox. As she hurried on her way, making the first-ever east-to-west crossing of the final segment of the Northwest Passage, her crew no doubt enjoyed many hot cups of coffee. Likely it was HBC-brand, but whitened with Pacific-brand condensed milk and sweetened with Rogers sugar, both iconic Vancouver-based products. The feat of two Canadian-built vessels, the Fort McPherson pulling alongside the Fort James to deliver supplies, is surely an epic watershed moment in Canadian arctic history. The fact that a photograph of its occurrence—recently located by the author and shown below— does not appear to have been publicized at any earlier date remains an unfathomable mystery.

(Library and Archives Canada Photo PA-203025 by Henry Lyall Smyth)

References and Acknowledgments

Most of the books, websites, archival sources, interview recordings and articles used for reference purposes are mentioned directly in the article or shown as notations on the exhibits and watermarks on the photographs.

All photographs and images used with permission or are in the public domain.

The writer used many articles found on Newspapers.com and from on-line copies of the Beaver magazine for reference and direct quotes as well as Herschel Island from Wikipedia.com particularly with respect to the history of Herschel Island.

The following books, articles and reports were used as sources for the article:

Baychimo Arctic Ghost Ship by Anthony Dalton

Arctic Trader by Philip H. Godsell

A Gentleman Adventurer The Arctic Diaries of Richard Bonnycastle by Heather Robertson

Lure of the North by Richard Finnie

The Big Ship by Henry Larson

Personality Ships of British Columbia by Ruth Greene

Ten Years in the High Canadian Arctic by Cecil E. Bradbury

Bent Props and Blow Pots by Rex Terpening

The Friendly Arctic by Vilhjalmur Stefansson

Klengenberg of the Arctic by Christian Klengenberg

The Making of an Explorer George Hubert Wilkins and the Canadian Arctic Expedition by Stuart

E. Jenness

I. Nuligak the Autobiography of an Canadian Eskimo by I. Nuligak

Fur Trade Posts of the NW Territories 1870-1970 by Peter J. Usher

Aux. Schooner Ruby – Arctic Supply Voyage by Capt. Ed. Shields from The Sea Chest Journal of the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society December, 1977

Canada’s Western Arctic – Report on Investigations in 1925-26, 1928-29 and 1930 by Major L.T Burwash

HBC Report: Western Arctic District Inspected July 6th – December 29th. 1923 by P.H. Godsell

HBC Post Journals (Tree River -1927), King William Island (1928, 1929 & 1930) Annual RNWMP and RCMP Reports – from 1913 to 1935

Harbour and Shipping magazine May 1927, page 222

In Memory of Ian Mor MacDonald by Doreen Riedel, RCMP veteran’s website.

The Ramblings of a “Matelot” by Reginald Harold Fricker, RN Communications Museum/Library website.